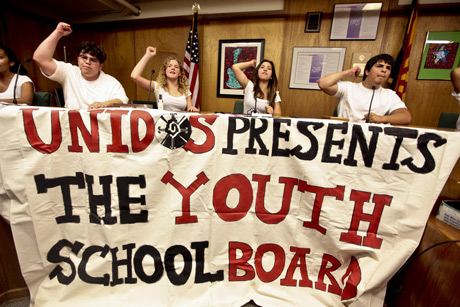

The students were tired of being ignored by the Tucson public school board, so they turned up the volume. Before the board members could sit down for their April 26 meeting, nine students and alumni of Tucson schools rushed to the front of the room, sat down in front of the microphones at the board members' seats and chained themselves together. A security guard grabbed two young women leading the charge, but they both wriggled free and locked down. Cheers rang through a crowd gathered in the lobby. “Occupy, occupy!” More than 100 students, parents and supporters rushed in, and soon the boardroom was packed wall to wall with protesters chanting and waving signs. “Our education is under attack! What do we do? Fight back!” The nine students threw their fists in the air and declared themselves the new school board in Tucson.

UNIDOS members push past a security guard before locking down. (Photo: Shachaf Polakow)

The school board was scheduled to vote on a resolution that would turn Mexican-American Studies (MAS) classes back into elective courses that would no longer provide students with core credits toward graduation. MAS supporters say the resolution is an attempt to compromise with a state law concocted by Republican Tom Horne, Arizona's former state schools' superintendent, to crush MAS at Tucson public schools. African-American, Pan-Asian and Native American studies courses are also taught as ethnic studies courses, but MAS is clearly Horne's target. Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer signed the law, commonly called HB 2281, in April 2010, soon after she signed the infamous SB 1070 bill that gave police the power to ask suspected illegal immigrants for papers, until the US Justice Department tied the law up in court.

Listen to a radio interview about this story, produced in partnership with Vocalo.

Board members canceled their meeting after the nine students, all members of the local youth group United Non-discriminatory Individuals Demanding Our Studies (UNIDOS), made it clear they would not get up until they were guaranteed that the Mexican-American classes they love wouldn't be downgraded to voluntary electives that could be lost all together in the coming waves of state budget cuts. The action was a temporary victory for UNIDOS. The group postponed a vote on a resolution that they say would put their heritage second to a whitewashed version of history that so often ignores the achievements and struggles of immigrants and people of color.

Nine members of the youth group UNIDOS took over the April 26 Tucson school board meeting and declared themselves the new school board, the latest action in a campaign to save Mexican American Studies classes. (Photo: Shachaf Polakow)

“We will no longer tolerate it if our histories, our songs, our knowledge would be taught at second-class courses,” Tucson High alumni Leilani Clark told supporters while chained to her seat at the head of the boardroom. “There is an undeniable fact that we have a Eurocentric bias in our education … We don't see our faces in these books, and we don't see our faces in our lessons plans until we walk into an Ethnic Studies class.”

Students and UNIDOS members routinely take time out of their busy schedules to attend school board meetings and speak out in defense of their classes. The school board continued to disappoint them: first they announced that all ethnic studies classes would be in compliance with the law created to cancel them and then they refused to join a lawsuit filed by 11 MAS teachers against the state. With a ruling on whether MAS classes were in compliance with HB 2281 expected by mid-May, UNIDOS members said the board was succumbing to state bullying and attempting to avoid losing millions in state funding by downgrading the classes to second-rate electives.

UNIDOS member Daniel Montoya addresses the supporters filling the school board meeting room. (Photo: Shachaf Polakow)

The boardroom takeover revealed the diverse community supporting MAS and the bold activists in UNIDOS. School officials, parents, students, local activists and two sympathetic school board members occupied the room for more than two hours. Music and song broke out, speeches were made and a general party was thrown in the face of the educational establishment. If these students are the truly the rabble-rousing radicals that enemies of MAS like Horne make them out to be, then something incredible is happening in Tucson communities, because the disruption had the full support of parents, neighbors and even politicians.

“I couldn't be more proud of these students,” said state Sen. Steve Gallardo, who had attended the meeting to oppose the resolution and promote legislation he has introduced to repeal HB 2281. “They sent a loud message all the way to the capital that Ethnic Studies needs to be revisited.”

UNIDOS chained themselves to their seats before presenting their demands. (Photo: Shachaf Polakow)

Parents of the UNIDOS members defended the young activists during a press conference after the successful action caused a shake up in the local media. Horne has pointed to other actions organized by students as evidence that MAS classes radicalize the youth and promote “ethnic solidarity,” but parents of the UNIDOS members say their kids are simply trying to be heard.

“How can you condemn Ethnic Studies as radical behavior?” asked Ernest Clark, father of Leilani Clark, during the press conference. He said the students acted in the spirit of civil disobedience established by civil rights leaders like Ghandi, Martin Luther King and Cesar Chavez. Clark taught in Tucson public schools for 32 years and was inspired by the UNIDOS members' eagerness to defend their education. “I saw those student's eyes, so eager to learn and it's so much better than seeing sad, lethargic eyes that have given up hope.”

UNIDOS activist Jesus “Nacho” Vejar celebrates his new spot on the Tucson school board. (Photo: Shachaf Polakow)

The festive action was the latest in a string of protests, sit-ins and demonstrations in support of the MAS program. No arrests were made, but Tucson police said they are reviewing video of the action and could press charges. In a time when Republicans in Arizona are defending SB 1070 and pushing legislation aimed at dehumanizing Mexicans and immigrants, fighting the ban on MAS has given students the perfect chance to show their collective strength. The struggle has gone on for years as Horne, who touted his anti-MAS and anti-immigrant stances to win the election for state attorney general last year, pursued a vendetta against the MAS program without ever entering a classroom.

Students, parents and other supporters filled the school board room in support of UNIDOS. (Photo: Shachaf Polakow)

The Audit

Two auditors showed up at Pueblo Magnet High School in Tucson on April 12 to attend a MAS class on social justice. Lisette Cota, a Pueblo High senior and UNIDOS member, was busy with a research project on the origins of negative stereotypes that affect local perceptions of her public school, where a majority of the students are of Mexican and Latino descent. Cota said the auditors sat through lessons and circled around different groups of students working on their research projects, silently taking notes on their work and discussions.

“It felt like we couldn't speak our minds,” Cota said of the audit later that day, sitting in with her father, Richard, at a local café. “It's like an invasion of your space … it was out of everybody's comfort zone.”

The auditors, two women with fresh state contracts, did not talk to the students or instructor and the students were told not to speak to them.

“It was scary,” Cota said, recalling the silent auditors. “If they write down one wrong thing, then we won't have our classes.”

The audit is a climax in the five-year battle between Horne and the MAS department in Tucson schools. Horne tried to ban the classes for years, claiming the program promotes anti-American ideas and radicalizes students of color by teaching them that they are members of an oppressed minority. He helped design HB 2281, which bans any classes that “promote the overthrow of the US government,” “promote resentment toward a race or class of people,” “are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group” or “advocate for ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.” Horne points to the presence of books like Paulo Freire's “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” in the MAS curriculum as evidence that MAS classes promote sedition and “ethnic solidarity.” If the auditors that attended Cota's class find MAS classes in violation of HB 2281, the school district could lose 10 percent of its state funding every month until changes are made to the curriculum.

HB 2281 took effect on Dec. 31, which happened to be Horne's last day as superintendent and, hours before leaving office, he hastily declared the MAS program in Tucson out of compliance with law. Horne presented only flimsy evidence for his non-compliance order, so current State Superintendent John Huppenthal, a Republican who made campaign promises to end MAS, decided to hire a private consulting firm to audit the program. The results of the audit were initially postponed until mid-May.

Students like Cota say Horne and Huppenthal should take the time to attend a MAS class before lashing out. The students say the classes have helped them develop a love for learning by connecting them to a shared history long ignored by public education. The classes do serve the interests of the growing Mexican-American population in Tucson schools, but they are open to any student of any race seeking a different perspective on culture and history.

Cota, whose grandparents emigrated from Mexico in the 1950s, said she signed up for a history class in the MAS program by accident after transferring from a private school to Tucson's Pueblo High. She was initially concerned that the class, which explores US history with an emphasis on the Chicano and Latino experience, would not prepare her for college the way a traditional politics or history class would. But she gave the program a try and it changed the way she looked at education and her own Mexican heritage.

“I didn't know anything about my history at all,” Cota said. “I was barely speaking Spanish at all. But when you learn about what your people actually do, I thought wow, I can do that too.” Cota said that she “hated” school before taking the MAS classes, but now she loves to read and has a new interest in history, an interest that grew after she learned about her people's place in the American story. “It was interesting to learn that there are people of my color in history that I hadn't learned about,” she said.

Cota enjoyed the history class so much that she signed up for literature class in the MAS department. There, she fell in love with “The Circuit,” Francisco Jimenez's collection of short fiction revolving around the life of a migrant child and “Zoot Suit,” a play by Luis Valdez based off the real-life Sleepy Lagoon trial and the Zoot Suit riots during the 1940s in Los Angeles.

“Once you start one of those ethnic studies classes, you just don't go back, because it has so much passion and those teachers have so much passion,” Cota said.

It's difficult to quantify the value of a student like Cota falling in love with school and learning, but hard numbers do show that MAS teachers are doing something right. Recent analysis of the program shows that students who completed a MAS class during their senior year were more likely to graduate than their peers. Over a six-year period, 5 to 15 percent more MAS students passed state reading and writing tests than students who did not take the classes.

Cota will graduate this year and go on to study psychology at the University of Arizona. She plans to minor in Mexican-American studies and possibly go to graduate school to become a librarian. “I kind of want to work in a museum,” she said.

Cota's social justice class that was recently audited is a capstone course designed to turn ideas into action. Now Cota is taking her social justice lessons from the classroom and into the world, where she has become an activist in a very public struggle to learn. Cota did not lock down with the students who took over the school board meeting, but she was there to join the protest and answer questions for the media. Cota said she never thought she would ever be so interested in her schoolwork, let alone become an activist, but her MAS classes inspired her to get involved with issues at her school.

Cota is well-spoken, well-dressed and splits up her time as an activist with other extracurricular activities like working with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and tutoring other students in English. She said the MAS classes do not turn students into radicals, as Horne contends, but critical and independent thinkers who ask tough questions about world around them.

“[Horne] calls us radicals, but he's so radical it's ridiculous,” Cota said before engaging her father in a discussion on the notoriously wacky world of Arizona state politics. “Even though there are these perceptions that we are radicals … they have to realize that we are human beings and we have thoughts and feelings and perceptions ourselves.”

The Teachers

“We can say Chicano studies is a verb, it entails action,” said Norma Gonzalez, who teaches Chicano literature at two Tucson high schools. “What could be a source of controversy is that students are getting active in democracy.”

Gonzalez said that, in MAS classes, students learn camaraderie and what needs to be done for positive transformation in society. By connecting students with their roots and teaching them about the struggles of the past, teachers like Gonzalez help students learn how to take part in a democratic process. “They can act as the people before them have … they have a responsibility to future generations,” Gonzales said.

Gonzalez said the numbers of Chicano and Latino students are increasing in public schools in Tucson and across the nation, and if these students learn to be critical thinkers, then the status quo smells a threat.

For Sean Arce, the MAS program director, it's obvious that the battle over ethnic studies in Tucson schools has been brewing for a long time. “The history of Mexican and Chicano studies in public school is a history of racism and subjugation,” Arce said.

Tucson has a rich history of activism surrounding Mexican-American education and activists worked for decades to introduce classes first to the University of Arizona and later to the K-12 public schools.

Conflict with Horne has been brewing for a while too, Arce said. In 2006, Tucson High School invited farm labor leader and civil rights activist Dolores Huerta to speak. Huerta offered commentary on the latest round of anti-immigrant legislation that was making its way through the Arizona legislature at the time and, at one point, said, “Republicans hate Latinos.” Arce said the media took the quote out of context and it enraged Superintendent Horne.

Horne sent his Deputy Superintendent, Margaret Garcia-Dugan, a Latina woman, to speak at the school and counter the idea that Republicans have something against Latinos. Horne's office instructed Tucson High students to keep silent during Garcia-Dugan's speech and to send any questions to his office in writing two weeks in advance. To protest this censorship, about 50 students duct taped their mouths shut, stood up and turned their backs on Garcia-Dugan and walked out of the auditorium.

“That started the ball rolling,” said Arce, who believes Horne has used his fight to ban the ethnic studies program to advance his political career.

Students continued to embarrass Horne, and in the spring of 2010, they formed a human chain around the school district headquarters to prevent Horne from holding a press conference celebrating the passing of HB 2281.

Horne was elected to state superintended in 2002 after promising to ban bilingual education in Arizona schools, and Horne kept his promise amid national controversy. His campaign against MAS and ethnic studies garnered national attention as well, and he touted the controversy in a successful campaign for attorney general.

Arce and Gonzalez are two of the 11 MAS faculty involved in a lawsuit against the state of Arizona. They invited the Tucson school board to join the lawsuit, but the school board refused. The teachers are challenging both the audit and the constitutionality of HB 2281. The case could take months, even years, but a final ruling on the whether MAS is in compliance with HB 2281 could come down in a matter of weeks. Gonzalez said it is still business as usual in her classroom, but the controversy has had a “chilling effect.” Whatever the outcome of the lawsuit and the audit, the Tucson students and teachers have made it clear they will not give up their classes without a fight.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.