Part of the Series

The Public Intellectual

Increasingly, Americans live in an era in which every aspect of society displays symptoms of political, economic and ethical impoverishment. This condition extends from the workplace and education to the legal system and the larger culture. It is evident in the way our society has increasingly become dominated by the language of extreme nationalism, racism, nativism and grotesque levels of inequality. And it is evident in the depoliticizing conditions of our social order that strip individuals of critical thought, self-determination and reflective agency.

In the current era, politics is no longer about the language of public interest, but about how to survive in a world without social provisions, support, community and a faith in collective struggle. This is a language that operates in the service of violence, and marks, to quote author Bill Dixon, “a terrifying new horizon for human political experience.” This is a language that is horrifying for producing without apology what the end of politics, if not humanity itself, might look like. Under such circumstances, democracy is not merely under siege, but is close to being erased.

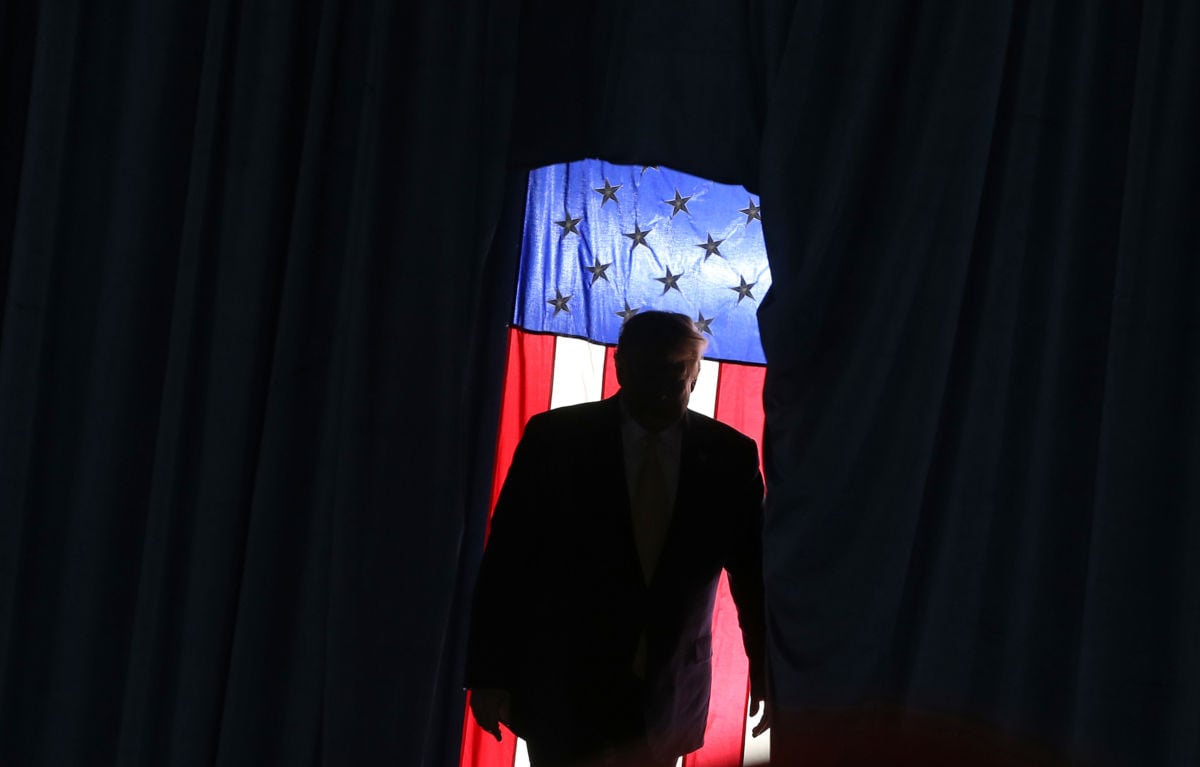

Examples of such violence abound in the United States under the presidency of Donald Trump, who has promised to cut in his budget over a trillion dollars in support of Medicare and Medicaid. He has also, relentlessly attacked the Affordable Care Act resulting in nearly 2,000,000 more people being uninsured and a proposed $4.5 billion cut from federal spending on food stamps over five years. Moreover, the Trump administration continues to endanger the planet by rolling back clean water protections created to regulate the use of polluting chemicals near bodies of water.

Other examples include the White House asking the Supreme Court to end DACA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program, which provides immigration protections for over 700,000 undocumented young people who were brought to the United States as children. There is also a recent Supreme Court ruling allowing the United States to deny asylum to people who pass through another country on their way to the U.S. — a decision that turns away most Central American migrants who arrive at the southern border.

In this unapologetic authoritarian regime, the language of violence, cruelty and hatred has reached new levels. For instance the New York Times reported that Trump suggested shooting immigrants in the legs in order to prevent them from crossing the Southern border.

It gets worse. Trump also ordered the ending of the “medical deferred action” program which allows immigrants who are seriously ill to extend their stay in the U.S. by two years in order to receive much-needed medical treatment. Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey captured the cruelty of such a policy in his statement that the Trump administration is now “literally deporting kids with cancer” and that this policy would “terrorize sick kids who are literally fighting for their lives.” The administration walked its position back after fierce criticism, but the underlying intent is unmistakable.

Trump and his allies appear to delight in asserting power through acts of cruelty that threaten, disrupt, and condemn entire populations to a politics of disposability and spheres of terminal exclusion. Among the many instances of this type of cruelty is Trump’s deportation of 200,000 Salvadorian immigrants as part of his policy of ending the humanitarian program known as the Temporary Protected Status policy.

Effects of the Predatory Culture of Neoliberalism

There is more at work here than a fascist politics of disappearance. There is also an attack on modes of critical agency and on the educational and cultural institutions that create the conditions where citizens can be informed in order to make democracy possible. Under these pressures, people become susceptible to modes of agency that embrace shared fears, the loss of autonomy and rancid hatreds rather than collective values and obligations.

Market fundamentalism has turned the principles of democracy against itself, twisting the language of autonomy, solidarity, freedom and justice that make economic and social equality a viable idea and political goal. Neoliberalism produces a notion of individualism and anti-intellectualism that harbors a violent disdain for community and, in doing so, reinforces the notion that all social bonds and their respective ethos of social responsibility are untrustworthy. Unchecked notions of self-interest and a regressive withdrawal from a substantive oppositional politics now replace notions of the common good and engaged citizenship, just as “existing political institutions have long since ceased to represent anyone but the wealthy.” Under the reign of a market fundamentalism, social atomization becomes comparable to the death of an inclusive and just democracy.

Closely related to the depoliticizing practices of neoliberalism, the politics of social atomization and a failed sociality is the existence of a survival-of the-fittest ethos that drives oppressive narratives used to define both agency and our relationship to others. Mimicking the logic of a war culture, neoliberal pedagogy creates a predatory culture in which the demand of hyper-competitiveness pits individuals against each other through a market-based logic in which compassion and caring for the other is replaced by a culture of winners and losers, with the former assuming the status of a national sport, if not religion. As Hartmut Rosa observes, under neoliberalism:

People perceive the world around them, the world they encounter, as a combat zone to be viewed at best with indifference but more often with hostility — a world in which their own position was always precarious anyway — they see the vital, the foreign, the strange that confront them as a danger and a threat. Indeed, their own very real experience has led them to associate change above all with decadence and decline.

The language of aggression replaces matters of concern for those deemed “other” by virtue of their class, ethnicity, religion, race or non-participation in a consumer society. Underlying this neoliberal worldview is a militaristic mentality that replicates reality TV’s mantra of a “war of all against all,” which brings home the lesson that punishment is the norm and compassion the exception. Yet, this rhetoric of command does more than pit individual against each other in an endless loop of competitiveness and a world in which there are only individual winners; it also weakens public values and reinforces a hardening of the culture, one in which a self-righteous coldness takes delight in the suffering of others.

How else to explain Trump’s racist comments and cruel policies aimed at undocumented immigrants trying to escape from poverty, violence, gangs and rogue societies? How else to explain separating children from their parents at the border and then jailing them in concentration camps? The predatory culture of hyper-competitiveness produces a weakening of democratic values, pressures and ideals, and in doing so, creates a culture in which expressions of violence and cruelty replace the ability to act politically, responsibility and with civic courage. This predatory culture furthers the process of depoliticization by making it difficult for individuals to identify with any sense of shared responsibility and viable notion of the common good.

Attacks on the Institutions That Make Democracy Possible

Democratic public spheres such as the oppositional media, schools and other public institutions are disappearing under the toxic policies of austerity and privatization thus reinforcing a hyper-individualized, masculine and militarized culture that destroys notions of engaged and critical citizenship, along with any viable sense of individual and social agency. Operating under the false assumption that there are only individual solutions to socially produced problems, neoliberal pedagogy reinforces depoliticizing states of individual alienation and isolation, which increasingly are normalized, rendering human beings numb and fearful, immune to the demands of economic and social justice and increasingly divorced from matters of politics, ethics and social responsibility. This amounts to a form of depoliticization in which individuals develop a propensity to descend into a moral stupor, a deadening cynicism, all the while becoming increasingly susceptible to political shocks, and the seductive pleasure of the manufactured spectacle.

In this instance, the political becomes relentlessly personal, rendering difficult any notion of social agency and collective resistance. There is more at work here than a freezing of the capacity for the development of modes of critical agency; there are also signs of widespread apathy as more and more people refuse even the most elementary appeals to participate in elections or educate themselves about politics. Meanwhile, we see the slow deterioration of public spheres that once offered at least the glimmer of progressive ideas, enlightened social policies, non-commodified values and critical exchanges. As public institutions and values are undermined, unions are weakened, working people lose their jobs with no tools to prevent such losses from happening, and increasingly all that is left is a culture of unfocused anger, despair, immediacy and entertainment, which infantilizes everything it touches.

As the connections between democracy and education witherrather than working to improve the conditions that bear down on one’s life and society in general. Dealing with life’s problems becomes a solitary affair, reducing matters of social responsibility to a regressive and depoliticized notion of individual choice. As the social sphere is emptied of democratic institutions and ideals, apocalyptic visions of fear and fatalism reinforce the increasingly normalized assumption that there are no alternatives to existing political logics and the tyranny of a neoliberal global economy. Under neoliberalism, shared notions of solidarity are erased along with institutions that nurture an engaged and critical sensibility. This type of depoliticizing erasure raises several questions: Can a democratic conception of politics emerge? How does it happen? And what agents of change are available to take up the task of mass and collective resistance?

Within this neoliberal populist political formation, language functions to repress any sense of moral decency and connection to others; as a result, individual communication rooted in democratic values and dialogue loses all meaning. Individuals, Leo Lowenthal argues, are pressured increasingly to act as “ruthless seekers after their own survival, psychological pawns and puppets of a system that knows no other purpose than to keep itself in power.” Critical agency is now viewed as dangerous and undermined by the ongoing neoliberal pedagogical machineries of power and a culture of manufactured ignorance that works as to produce a form of political repression, on the one hand, and political regression and infantilism on the other.

The Dangers of Depoliticization

Depoliticization turns ignorance into a virtue, making it all the more difficult for individuals to balance reason and affect, distinguish between fact and fiction, and make critical and informed judgments. Increasingly, education both in schools and in the wider cultural apparatuses, such as the mainstream and conservative media, becomes a tool of repression and serve to promote and legitimate neoliberal fascist propaganda. As such, the never-ending task of critique gives way to the failure of conscience, while succumbing to simplistic views of the world defined through an irrationality that is at the heart of a fascist politics. Reason and informed judgment, once a precondition for creating informed citizens, gives way to a culture of shouting, emotional overdrive and shortened attention spans. New digital technologies and platforms controlled by monopolies trade in consumerism, speed, and brevity and conspire to make thoughtfulness, if not thinking itself, difficult. Knowledge is no longer troubling; instead, it is pre-packaged in the 24/7 news cycle reduced to babbling one-liners and commercial smart bombs.

As neoliberal ideology works its way through the vast reach of the mainstream and conservative media, it operates as a disimagination machine that attempts to both control history and erase moments of resistance and oppression. History as an act of dangerous memory is whitewashed, purged of utopian ideals and replaced by apocalyptic fantasies. These include narratives of decline, fear, insecurity, anxiety and visions of imminent danger, often expressed in the language of invasion, dangerous hordes, criminal and disease-infected others. As public vocabularies and transcripts disappear, it is difficult for individuals to understand historically the multiple wars waged on democratic ideals. Everything appears to lack any antecedents, making the poisonous vitriol and policies of neoliberal fascism more energizing, fresh and free of a toxic history.

Rather than revealing humanity’s legacy of repression and violence, or its heroic moments of resistance, memory is trapped in the present. The politics of depoliticization — with its refiguring of the social sphere, individual responsibility, historical memory, critical thinking and collective identity — now begins to take the form of an acute indifference, withdrawal from public life and a disdain for politics that amounts to a political catastrophe. The move from crisis, which implies the possibility of change, to catastrophe in which there are present agents necessary for a radical restructuring of society, is disappearing. In a society increasingly marked by a flight from responsibility, the ethical duty to care for the other vanishes or is viewed with disdain. In short, matters of self-fulfillment and an egoistic self-referentiality work hand in hand with instances of “painless morality” or an empty morality stripped of ethical obligations and an attentiveness to social costs.

We live in a neoliberal age that destroys the most important democratic institutions, values and relations that connect us. This is evident in the overwrought concentration of power and wealth among the 1 per cent with its corollary in corporate-induced corruption that leads millionaire politicians such as Trump to believe that he is above the law and can disregard the constitution and separation of powers. This is apparent in Trump’s refusal to cooperate with the impeachment process taking place in the Congress. It is also evident in the institutional, political, and cultural practices that delight in the merging of violence and power to enact a cruelty upon entire populations — women, immigrants, children, Blacks, and Muslims. In addition, this form of cruelty is evident in the recent Supreme Court decision that reinforces Trump’s brutal asylum policies.

Other examples of the current culture of cruelty can be found in the opioid crisis, produced largely for the profits of drug companies. These are companies that traffic in death, and in the rising of suicide rates due to what Anne Case and Angus Deaton labeled “deaths of despair.” Such deaths are largely caused by social isolation, disenfranchisement, poverty, lack of meaningful jobs, stagnant wages, and cuts in social programs due to tax breaks for the rich and oversized corporations.

Cruelty is one of the threads that is closely tied to the workings and legitimation of a fascist politics, as can be seen under modes of governance enacted by demagogues such as Trump, Bolsonaro, Erdogan and others who have elevated cruelty and violence to a national ideal.

Democracy as both a promise, activity and ideal is in retreat around the globe, given how it is continually undermined by neoliberal capitalism. Astra Taylor is right to argue that “the massive financial inequities it creates dismantle hard-won democratic gains.” In societies where market values are considered more important than democratic values, hope only lives amid the darkness of the moment. Without hope there is no possibility for resistance, dissent and struggle. Agency is the condition of struggle, and hope is the condition of agency. Hope expands the space of the possible and becomes a way of recognizing and naming the incomplete nature of the present.

When hope dies, what is also lost is a viable sense of those essential social spheres, public goods, historical consciousness and collective forms of support necessary for an active and engaged citizenry.

Preconditions for Resistance

The problem of agency is a precondition for any viable form of individual and collective resistance. It is also crucial to address changes in consciousness and to rethink the issue of historical and collective agency as part of the struggle for structural change. Ideological and structural changes can only take place through a formative culture and those institutions and public spheres that make education central to politics itself. The indifference to a discourse regarding who are the historic agents of change in the current moment is not merely deficient politically, it is also complicit with the rise of right-wing authoritarian movements.

What emerges in the absence of these institutions, public narratives and democratic spaces is a neoliberal fascist politics and culture. This new political formation and punitive monstrosity is defined by the glitter, cruelty, spectacles, commodification, technological fanaticism, regressive notions of privatization and disembodied notions of individualism that dethrone what Hannah Arendt has called “the prime importance of the political.” As Frederick Douglass once said, “it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder… the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed.”

Such resistance is making its appearance forcefully in the current moment. Young people are fighting ecological destruction, disenfranchised educators are challenging pedagogies of oppression, and cultural workers around the globe are revolting against the rising tide of fascist politics.

In this context, these agents of change are building new alliances with working classes who are exercising more radical forms of collective resistance in the struggle for an economic democracy and socially just society. The plague of a fascist politics and its politics of depoliticization may be on the move, but as Marx once said, history is open. In the current historical conjuncture, ample possibilities are emerging to recognize that the current crisis of agency is a precondition for addressing not only the crisis of education and politics, but also the crisis of democracy itself. Only then, as Douglass pointed out, can “the conscience of the nation … be roused” and the plague of neoliberal fascism challenged and overcome.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.