Recently, I have been trying to navigate my own journey toward calling for the next phase in the education reform debate—the primary tension being between my evolving position as it rubs against my sisters and brothers in arms who remain (justifiably) passionate about confronting the misinformed celebrity of the moment or the misguided journalist of the moment.

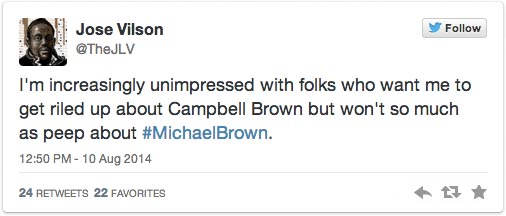

And then Jose Vilson posted on Twitter:

This moment of concise clarity from Vilson was followed the next morning by a post on R.E.M.’s Facebook page, Troopers release video showing forceful stop of musician Shamarr Allen:

As he continued defending his troopers’ actions, the Louisiana State Police chief released a dashcam video Tuesday of the forceful stop of a musician in the Lower 9th Ward.

Shamarr Allen, a trumpeter known for his band, Shamarr Allen and the Underdawgs, has claimed in TV interviews that he felt in danger and that he was treated unfairly because of his race.

“It’s just wrong,” Allen told NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune on Tuesday after watching the video. “I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, I don’t do none of that. I don’t live wrong at all. It’s just, this is the life of a black man in the Lower 9th Ward.”

Occurring with cruel relevance at the nexus of disaster capitalism and education reform, New Orleans, Allen’s “life of a black man” rests in the wake of Michael Brown’s death as a black young man:

An 18-year-old Missouri man was shot dead by a cop Saturday, triggering outrage among residents who gathered at the scene shouting “kill the police.”

Michael Brown was on his way to his grandmother’s house in the city of Ferguson when he was gunned down at about 2:15 p.m., police and relatives said.

What prompted the Ferguson officer to open fire wasn’t immediately clear.

Multiple witnesses told KMOV that Brown was unarmed and had his hands up in the air when he was cut down.

The officer “shot again and once my friend felt that shot, he turned around and put his hands in the air,” said witness Dorian Johnson. “He started to get down and the officer still approached with his weapon drawn and fired several more shots.”

This feeling has come to me before, a sense that outrage remains mostly token outrage, misguided outrage. Outrage over Whoopi Goldberg, Campbell Brown, and Tony Stewart filled social media, blacking out Brown and Allen as well as dozens and dozens of black men who will never be named.

50 Years Later: “you must consider what happens to a life which finds no mirror”

August of 2014 marked the month James Baldwin would have turned 90. 18 December 2014 will be 50 years since Baldwin spoke at The Non-Violent Action Committee (N-VAC) (speech archive):

There Baldwin built a passionate message, challenging his audience with “you must consider what happens to a life which finds no mirror.” Baldwin inspired author Walter Dean Myers, who echoed a similar message early in 2014 just before his own death:

But by then I was beginning the quest for my own identity. To an extent I found who I was in the books I read….

But there was something missing. I needed more than the characters in the Bible to identify with, or even the characters in Arthur Miller’s plays or my beloved Balzac. As I discovered who I was, a black teenager in a white-dominated world, I saw that these characters, these lives, were not mine. I didn’t want to become the “black” representative, or some shining example of diversity. What I wanted, needed really, was to become an integral and valued part of the mosaic that I saw around me….

Then I read a story by James Baldwin: “Sonny’s Blues.” I didn’t love the story, but I was lifted by it, for it took place in Harlem, and it was a story concerned with black people like those I knew. By humanizing the people who were like me, Baldwin’s story also humanized me. The story gave me a permission that I didn’t know I needed, the permission to write about my own landscape, my own map.

There is a beauty, a symmetry to the lineage from Baldwin to Myers—and then to the countless young people for whom Myers paid it forward.

But I must pose a counter-point about Baldwin’s speeches and essays: Why must Baldwin remain relevant 50 years later?

Baldwin’s words in 1964—”it is late in the day for this country to pretend I am not a part of it”—fit just as well in Allen’s mouth, pulled over in New Orleans because he committed the crime of approaching his car and then reversing himself while black.

And then Baldwin in 1966, A Report from Occupied Territory:

Here is the boy, Daniel Hamm, speaking—speaking of his country, which has sworn to bung peace and freedom to so many millions. “They don’t want us here. They don’t want us—period! All they want us to do is work on these penny-ante jobs for them—and that’s it. And beat our heads in whenever they feel like it. They don’t want us on the street ’cause the World’s Fair is coming. And they figure that all black people are hoodlums anyway, or bums, with no character of our own. So they put us off the streets, so their friends from Europe, Paris or Vietnam—wherever they come from—can come and see this supposed-to-be great city.”

There is a very bitter prescience in what this boy—this “bad nigger”—is saying, and he was not born knowing it. We taught it to him in seventeen years. He is draft age now, and if he were not in jail, would very probably be on his way to Southeast Asia. Many of his contemporaries are there, and the American Government and the American press are extremely proud of them. They are dying there like flies; they are dying in the streets of all our Harlems far more hideously than flies.

Or Baldwin in 1963 asking, Who is the nigger?:

It is 2014 and the list of blacked out names grows—Trayvon Martin, Jordan Davis, Michael Brown—with the unnamed list even longer, although mostly ignored, invisible.

When Baldwin’s 90th birthday approached, many expressed how Baldwin as a writer and powerful public voice has himself become mostly unseen, unheard, unread, but each day suggests that in the US we prove Baldwin’s words to be disturbingly relevant.

At the end of his 1964 speech, Baldwin asserts: “[I]t is not we the American negro who is to be saved here; it is you the American republic, and you ain’t got much time.”

“I came to explore the wreck,” explains Rich’s speaker, the “wreck” a metaphor for the US:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth

the drowned face always staring

toward the sun…a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

The narrative of the US remains a redacted myth, names and lives blacked out. Yes, as Baldwin noted, “it is late in the day for this country to pretend I am not a part of it.”

Let us hope it isn’t too late.

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $29,000 in the next 36 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.