We all know an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind. But for Mothers for Justice and Equality, getting justice has never been about revenge. The Boston-based nonprofit was founded by Monalisa Smith, who lost her 18-year-old nephew, Eric Smith, to gun violence in 2010. Determined to end violence in their communities, the mothers who came together to form Mothers for Justice and Equality recognized early on that many of them had family members who were both perpetrators and victims. They recognized that they needed to take action into their own hands if they were to reduce community violence.

Needing answers to questions she had about her sister’s last moments alive, Chicago attorney Jeanne Bishop also took matters into her own hands. Over objections from her family, Bishop decided to write to and eventually to visit her sister’s killer, David Biro, in prison in Michigan. On April 7, 1990, Biro had killed Bishop’s sister, Nancy Langert, who was pregnant at the time, as well as Langert’s husband, Richard.

“The only justice that [David] could give [me] was to grasp the magnitude of what he took,” said Bishop in a telephone interview. She gave up a corporate job to become a public defender and is now an activist against gun violence and the death penalty as well. “The whole system is set up to keep victims and perpetrators separate,” said Bishop. She added, “No one wants offenders to say ‘I’m sorry’ to their victims.”

Smith and Bishop would be among the first to say that the current legal system is failing victims of violent crime. Truthout explored how they and others are forging new paths to heal harm.

What the Research Says

In the first-ever national survey of victims’ views on safety and justice, published in August 2016 by the Alliance for Safety and Justice, crime victims overwhelmingly said they support spending money on treatment and crime prevention instead of on prisons and jails. Two-thirds of victims of crime said they did not receive help following the incident, and those who did said it came from family and friends, not from the criminal legal system. While the survey noted that the Victims of Crime Act increased funding for victim services from $745 million in 2014 to $2.3 billion in 2015, money was not necessarily allocated to the communities most harmed by repeat crime and least supported by the legal system. Victims of crime are disproportionately low-income people, people of color and/or young people — the same groups that are most targeted by policing and incarceration.

Attorney Rahsaan Hall, Director of the Racial Justice Program for the ACLU of Massachusetts, said in an interview that the system fails victims because they are seen as a “commodity in the production of justice.” Victims are “run through the system for the sake of achieving a conviction,” Hall said. “Little time is dedicated to their healing or their restoration.” This healing is acutely necessary: The survey by the Alliance for Safety and Justice said 8 in 10 report experiencing at least one symptom of trauma. The survey pointed out that by a margin of 3-to-1, victims preferred holding people accountable with other options than prison; 2-to-1 preferred a justice system with more emphasis on rehabilitation than on punishment. And 61 percent favored shorter sentences.

Hall said that when he was a prosecutor, he had cases where victims of crime were reluctant to prosecute and he had to “charge ahead.” He added, “Prosecutors represent the ‘state,’ and even though the victim is the one who is harmed, the prosecutor still has to hold someone accountable. Victims who are reluctant to come forward are forced to testify in order for prosecutors to prove their case against the accused. So in some instances, the desires of the victim are not considered.”

How a Victim Fought Back

Jeanne Bishop was familiar with law as an attorney but was shocked when she suddenly found herself grappling with the system as a victim, a story she details in the book she wrote after her sister’s murder, Change of Heart: Justice, Mercy, and Making Peace with My Sister’s Killer.

“Victims have no advocates,” said Bishop, “unless there is a case situated in the prosecutor’s office. We have all these unmet needs until there is an arrest and often there isn’t an arrest…. Institutionally, involvement of victims is minimalized.”

Bishop said the questions she had about her sister’s last moments led her to seek out Biro, who was a juvenile at the time of the crime and sentenced to life without parole. Although the landmark 2012 case, Miller v. Alabama, stated that even children who commit the most heinous of crimes are capable of change and ended life without parole for juveniles, the case allowed for discretion in judges’ application of the law. For that reason, Biro’s second sentence — for an additional charge imposed because Langert was pregnant at the time of the murder — was a discretionary decision. As a result, Biro will never be released from prison.

At first, Bishop acknowledged in an interview with the Chicago Tribune, she could not say his name aloud for almost two decades. Biro would not admit his guilt in the brutal crime, she said. However, his correspondence with Bishop led to an epiphany about taking responsibility for what he’d done. Now, Bishop talks to Biro once a month and goes to visit him once every two to three months.

Bishop explained how important those visits are to her. “He said to me the other day, ‘The more I get to know Nancy through you, the worse I feel about what I did.’ To every person who has taken a human life I say you took this person out of this world so [for] every bit of good that they cannot do, you must … send out ripples of goodness.”

After Biro’s epiphany, he took stock of everyone he had hurt. Bishop said he has done everything he can to better himself. Early on, he earned his GED and played guitar. However, as scholars have pointed out, as incarceration numbers increased, punitiveness usurped rehabilitation, making pursuits like these unavailable.

“College classes, music, much of what he had, even a little typewriter was taken away. All he can do is read, write, reflect and try to be a good person,” Bishop added.

Bishop is quick to point out that she is not unique: Other people on the outside have developed substantial relationships with those behind bars who have committed violent crimes. She pointed out that Cindy Sanford, on a chance encounter with a prisoner artist, ended up getting to know the artist — a young man serving life in a Pennsylvania prison — and wrote to him. In her book entitled Letters to a Lifer, Sanford tells the story of how she and her family came to know him and eventually, to legally adopt him.

Taking Back the Community

Jeanne Bishop noted that it’s not only the families of victims, but also the families of incarcerated people, who must be supported.

“I go to a grave,” said Bishop, “but for a mother, when you see this person who you carried in your body in prison, and you are leaving them there, death is almost easier.”

Monalisa Smith, the founder of Mothers for Justice and Equality, concurred with Bishop, pointing out that a part of supporting victims’ families is recognizing that perpetrators’ families are also suffering.

“We do a lot of training to help people to move grief forward,” she said of her group. “Part of that is forgiveness and part of that is learning that there is a mother whose child went to jail. We meet together, mothers of victims and perpetrators, and our families.”

Since 2010, they have educated themselves in techniques of healing, mentoring, awareness, advocacy and peace-building. Mothers for Justice and Equality provides courses for leadership, supports a youth academy, finds employment for participants and takes ownership of the crisis of violence in neighborhoods by participating in solving it. In essence, the group trains mothers to be advocates, to go into the schools and prisons, and to work with the police.

When Truthout asked why they chose to work with the police, Smith said “One of our goals is to change systems and institutions that are working against change. We want to build a bridge. For example, we have done sensitivity training with the cadets. We have them understand what trauma really means.” She went on to mention how many mothers were triggered by yellow “crime scene” tape and worked with the police to change practices, such as getting trauma services on the scene immediately.

Smith told former Boston police commissioner Ed Davis, “You need to sensitize your officers. Yes, you need to do forensic gathering but you cannot leave victims uncovered. It traumatizes the community.” She said that they responded, covering the victim and crime scene with a tent instead.

“No more white sheets and little feet sticking out — that’s what we saw,” Smith said. “First responders … must understand, there is a mother there, a child there.”

A symbol of restorative justice in a community bridge project shows connecting hands. (Photo: Wikimedia)

A symbol of restorative justice in a community bridge project shows connecting hands. (Photo: Wikimedia)

Restorative and Transformative Justice

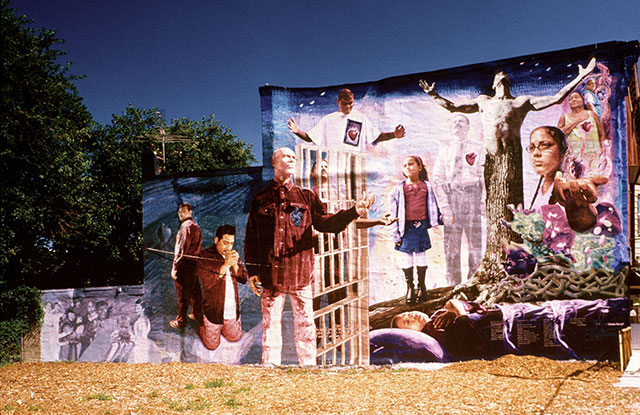

Mural Arts Philadelphia, which has created more than 3,800 works of public art, was pioneered by Jane Golden, its founder and executive director, who believes “art ignites change.”

One branch of Mural Arts is the Guild, a restorative justice project. Restorative justice is widely known as an attempt to provide healing and sometimes reconciliation to victims, their communities, and those who caused the harm. A goal for the Guild is to connect neighbors who have been affected by crime through shared creativity. Incarcerated or formerly incarcerated individuals, adjudicated teens or those on probation, create pieces of art alongside or simultaneously with other members of their respective communities. Their contributions give them voice and the murals help to shift public perception of those who cause harm.

In 2009, Concrete, Steel & Paint, a film about this program, explored how murals may be created in pieces but once they are hung, all parts fit together. This process of “restoration” through shared creativity forges bonds between those unlikely to connect otherwise, and promotes healing.

“Healing Walls: Prisoners’ Journey” from the film Concrete and Steel, is a Philadelphia mural that shows crime victims’ journey. (Photo: Jack Ramsdale)

“Healing Walls: Prisoners’ Journey” from the film Concrete and Steel, is a Philadelphia mural that shows crime victims’ journey. (Photo: Jack Ramsdale)

Transformative justice aims to go one step further than restorative justice, said Reverend Jason Lydon of the LGBTQ prison abolitionist group Black and Pink, at a September conference at Harvard Law School entitled, “Massachusetts and the Carceral State.” He added, “As a survivor of sexual violence, I can’t turn to the police to prevent harm because they don’t have the resources to make me feel better.”

“We can’t restore justice where there wasn’t justice already,” said Lydon, discussing the conclusions of generationFIVE, a group aiming to “interrupt and mend the intergenerational impact of child sexual abuse on individuals, families, and communities.” According to generationFIVE’s website, the organization strives to transform “social conditions that perpetuate violence — systems of oppression and exploitation, domination, and state violence.” Its members recognize that justice must demand institutional change.

Lydon said transformative justice might begin with survivor-centered work. “We need to make sure [survivors] have all the things they need to heal. A break from work if they need it, therapy, meals, medical care … resources and time.” He noted that holding the person who caused harm accountable is important. Part of what transforms is ensuring that the person who caused harm meets the demands of the person who was harmed. He also said that it is important not to demonize perpetrators, even if there are understandable feelings of hatred against them on account of their crimes.

Transformative justice-oriented activists stress that they are reclaiming the identity of their communities and restoring a sense of hope and purpose for future generations. Working outside of state systems, they are creating new models to heal harm.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.