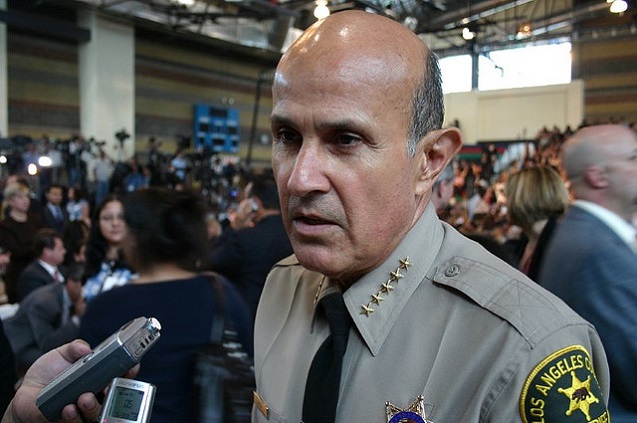

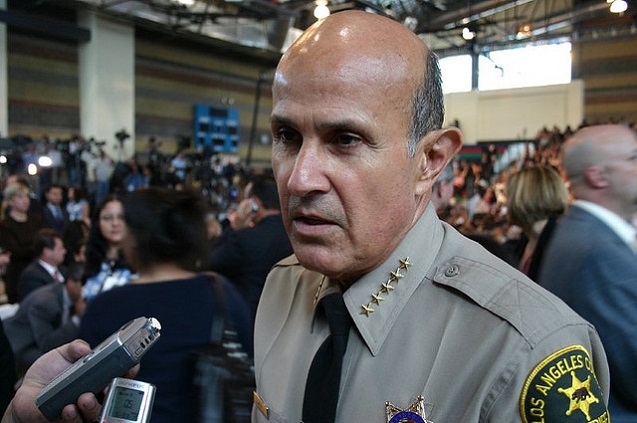

David Markland / L.A. Metblogs)” width=”637″ height=”423″ />Former Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca. (Photo: David Markland / L.A. Metblogs)

David Markland / L.A. Metblogs)” width=”637″ height=”423″ />Former Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca. (Photo: David Markland / L.A. Metblogs)

“To be an inmate in the Los Angeles County jails is to fear deputy attacks. In the past year, deputies have assaulted scores of non-resisting inmates, according to reports from jail chaplains, civilians and inmates. Deputies have attacked inmates for complaining about property missing from their cells. They have beaten inmates for asking for medical treatment, for the nature of their alleged offenses and for the color of their skin. They have beaten inmates in wheelchairs. They have beaten an inmate, paraded him naked down a jail module, and placed him in a cell to be sexually assaulted. Many attacks are unprovoked. Nearly all go unpunished: these acts of violence are covered up by a department that refuses to acknowledge the pervasiveness of deputy violence in the jail system.”

So begins the chilling September 2011 report compiled by the American Civil Liberties Union on conditions in Los Angeles County’s sprawling jail system. The report, along with the ACLU’s class-action lawsuit, touched off a media storm that resulted in the unexpected early retirement of long-time LA County Sheriff Lee Baca.

But the media reports weren’t news to Patrisse Cullors-Brignac, founder of Coalition to End Sheriff Violence in LA Jails. Police violence in LA’s poor communities of color, both in the street and in jails, has been rampant for many years, even if it only sporadically makes the news.

What is new is the perfect storm of factors that converged to bring hope for a change, and the activists who quickly seized on the opportunity. Between the unexpected vacancy in Baca’s post that threw open the election, media and legal scrutiny, and the proliferation of cellphone cameras and social media that often make instances of police violence previously unseen by the public en masse instantly viral, these activists are hoping the time is ripe to overhaul the way police interact with the communities they patrol.

The scandal culminated in February with a total of 20 indictments of former Sheriff’s Department officials, and federal investigations are ongoing.

“This [sheriff] race in particular is most competitive because of all the scandals,” Cullors-Brignac said. “Baca was going to win, now that he’s out . . . this race is up for grabs.”

There are no term limits for LA County sheriffs, and Baca has been at the department’s helm for 16 years. Whichever of the six candidates is elected could be in the position for many years to come.

“We have to do this right, and the sheriff has to see the community is going to hold them accountable,” Cullors-Brignac added. “We’re doing a really good job exposing it, now we need to formulate a new movement around accountability.”

When news of the scandal and Baca’s resignation broke, Cullors-Brignac’s group and others – such as the Youth Justice Coalition (YJC) – began organizing, prodding candidates to address the issues throughout a series of debates about everything from deputy violence, to oversight to incarceration of the mentally ill.

Chief among their demands is the creation of a civilian oversight board to provide independent reviews on use of force and misconduct complaints. The Coalition to End Sheriff Violence (C2ESV) commissioned a report from University of California, Los Angeles, law students under the guidance of law professor Tendayi Achiume, who oversees UCLA’s international human rights programs, exploring just that possibility.

“The key that [the Coalition is] pushing for is community involvement,” Achiume said. “They think that strong community involvement will mean there’s a spotlight on this going forward. If you look at the recommendations they make as to who sits on the board, they want community organizations to be involved in picking the people that sit on the board.”

The continued community mobilization and involvement, she said, would put pressure on the county Board of Supervisors both to create accountability and to catalyze the changes needed.

In December, the county responded to pressure from the indictments, investigations and media scrutiny by forming the Office of Inspector General, headed by seasoned public integrity division prosecutor Max Hunstman to handle complaints of use of force and misconduct. The proposed civilian oversight board would sit above Huntsman’s office in authority.

“Here in Los Angeles, if we’re able to implement this permanent civilian oversight body, we have the possibility of changing the ways in which sheriffs’ departments’ oversight is seen throughout the country.”

LA County Sheriff spokeswoman Nicole Nishida said the department is working with the Office of Inspector General (OIG) to “review and assess the potential role of an oversight board. We expect to have a report completed in late June for the Board of Supervisors. “

On Monday, May 19, the Coalition presented the county with its proposal to create a 9-member oversight panel composed of civilians, five selected by each of the county’s five supervisors and two by local criminal justice officials. Those seven would then select two more from candidates offered by community advocacy groups. The committee would also have on staff non-voting expert advisers who are researchers or people with law enforcement experience, according to C2ESV’s report, “A Civilian Review Board for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.”

With 18,000 employees, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department is the largest county sheriff’s department in the country, and change carries the potential of being influential on the national level.

“Here in Los Angeles, if we’re able to implement this permanent civilian oversight body, we have the possibility of changing the ways in which sheriffs’ departments’ oversight is seen throughout the country,” Cullors-Brignac said. “What Los Angeles does, the rest of the country does.”

Activists are also taking the opportunity to make proposals to county supervisors to reevaluate the prioritization of spending: devoting less money to cracking down and incarcerating people, and instead using funds to invest in economically-neglected communities that are often on the receiving end of police violence.

“LA County has the largest jail system in the world, and the highest-paid and most well-funded law enforcement – both the LAPD and LA sheriffs – in the world,” said Emilio Lacques-Zapien of the Youth Justice Coalition. “It’s an issue on so many different levels, from the spending priorities, to violence in the jails to [deputy] violence in the street, to sheriff’s deputy harassment and citations on the Metro, trains and buses. It’s everywhere.”

Lacques-Zapien asserted, “If you’re a young person of color in this city, and you don’t have access to resources, you’re going to encounter the Sheriff’s Department one way or another.”

The YJC is pushing the county to redirect a small portion of the spending on law enforcement toward youth jobs, intervention workers and youth centers, and a drastic reduction in arresting and jailing people for minor offenses. They’re also demanding that students of all levels have free access to public transit, since fare evasion is the leading reason for youth citations, and asking Attorney General Kamala Harris to create a special prosecutor to investigate cases of officer-involved shootings, use of force and misconduct.

“When there’s an injunction on an area, any group of people together in 3 or more can be labeled as a gang.”

Lacques-Zapien said a big issue for communities of color in the upcoming election is gang injunctions. Gang injunctions are court orders that restrict the activities of people labeled “gang members” by law enforcement. Critics contend they are a serious violation of civil liberties because police can label anyone a gang member without having to present evidence of wrongdoing and that often results in racial profiling. The YJC is advocating for a moratorium on them; Lacques-Zapien says they are akin to putting entire areas of the city on probation.

“When there’s an injunction on an area, any group of people together in 3 or more can be labeled as a gang,” he said. “Basically what they do is they profile and criminalize specifically black and brown youth in injunction zones; they stop and frisk them, ask them about their tattoos and what neighborhood they’re from. Whether or not they’re involved, the law enforcement officers can put them on a gang database.”

Violence in LA Jails

According to from the ACLU’s suit, “The [jail] violence is not the work of a few rogue deputies. Rather, it is a systemic problem that has continued unchecked for decades.” The documents state violent deputies had formed gangs, with everything commonly associated with street gangs, like tattoos and hand signals, and openly ruled at places like Men’s Central Jail and have done so since perhaps the 1970s.

Recent media reports revealed the culture that permitted deputy gangs to exist in jails had bled into the streets. In March, a female deputy filed a lawsuit claiming she was threatened and harassed by a group of patrol deputies calling themselves the Banditos.

Injuries sustained by inmates from deputy beatings include “broken legs, fractured eye sockets, shattered jaws, broken teeth, severe head injuries, nerve damage, dislocated joints, collapsed lungs and wounds requiring dozens of stitches and staples,” according to court documents. Inmates were called racial slurs and had joints popped out of place by beatings. The behavior was tacitly permitted by supervisory inaction.

Deputies beat inmate James Parker unconscious. They then charged him with assaulting them.

The deputies would cover violence up by filing false charges against inmates, according to Peter Eliasberg, legal director for the ACLU of Southern California. For example, Gabriel Carrillo, who was beaten while in handcuffs during an attempted jail visit from his brother, was charged with slipping out of his cuffs and attacking deputies. Eliasberg said wounds and bruises were photographed on Carrillo’s wrists that proved he was in fact beaten while handcuffed. Charges against Carrillo were dropped.

“Carrillo was facing years in the state prison, and the reality was, he was a victim of this, and he was the one who was beaten,” Eliasberg said.

ACLU jail monitor Esther Lim watched as deputies beat inmate James Parker unconscious. They then charged him with assaulting them. During the beating, Lim told The Los Angeles Times the deputies kept repeating the words “stop resisting” as though they were “reading from a script.”

According to the Times:

Lim said the ACLU commonly receives complaints from inmates who say deputies beat them while repeating “stop resisting” commands, even when the inmates aren’t resisting. Lim said she suspects the deputies involved in this incident recited the commands as a ruse to later justify their actions with the help of a jailhouse recording or other deputies who may have heard their commands.

Parker’s criminal case ended in a mistrial when the jury could not come to a unanimous verdict.

While Sheriff’s Department officials disagreed that incidents of inmate abuse were frequent and that there is a “culture of violence” in the department, Custody Assistant Sheriff Terri McDonald said each event or perception of a culture of misconduct needed to be addressed. In an emailed statement, McDonald wrote:

So many changes have occurred over the last two years, including revamping the use of force policy, including the review process; increased supervisors and funding for training staff; increasing the internal affairs/ICIB [Criminal Investigation Bureau] units to reduce their caseloads to expedite reviews; establishment of the IMPAAC [Internal Monitoring, Performance Audits and Accountability Command] unit; increased installation of video cameras in the jails. Over the last two years, the jails have experienced a significant decrease in inmate injuries during force incidents and the vast majority of force results in no injuries or allegations of unnecessary or excessive force . . . We take our charge of improving and demonstrating our commitment to the citizens of Los Angeles County seriously and remain committed to transparency and we continue to improve.

Civil rights attorney Cynthia Anderson-Barker said since the scrutiny began there has been some improvement, but added there is still a ways to go. “Apparently the beatings have gone down in the jails – which is a good thing – but out on the streets, things have not changed. There have been no changes,” she said.

Longstanding Issue

Problems in LA County’s jails and policing practices on the streets started long before Baca took office. To address longstanding issues in 1992, the county convened the Kolts Commission to review the Sheriff’s Department. Two decades ago, the commission found patterns that persist today, including “deeply disturbing evidence of excessive force and lax discipline” and the existence of deputy gangs. They found numerous cases in which large discrepancies existed between deputies’ personnel files and evidence presented in lawsuits about their abuse.

Twenty-two years later, according to ACLU documents, efforts to curb the problems using measures recommended by the Kolts Commission appear to have failed. Deputies had become so brazen about abusing jail inmates that they were beating inmates without trying to hide it from civilian witnesses like chaplains, visitors and jail monitors.

It was the beatings and false arrests of jail visitors that prompted 18 federal grand jury indictments against Sheriff’s deputies. Gabriel Carrillo’s 2011 beating was one that helped spark the probe.

But even with all the attention on the issue now, Anderson-Barker said the behaviors are so entrenched that it is almost impossible to get problem officers disciplined, let alone taken off the street.

“The first thing this country needs to admit is it has a long history of allowing racism and classism to formulate ideas of how police officers relate to the communities they serve. … The first thing is, let’s just admit that’s happening. It’s a national crisis.”

“You’ve got to change the culture,” Anderson-Barker said. “The problem to me, really at its core is holding officers accountable and disciplining them, which is frankly impossible with the police union, both for the Sheriffs and the LAPD. The bottom-line problem is discipline – changing the culture – and that’s going to be very hard to change with a review board. There will be a place for people to bring their concerns, but how will the offending officers change their behavior?”

After 23-year-old Carlos Oliva was shot and killed last year by deputies, it came to light that one of them, Tony Forlano, had been involved in six other shootings. After Forlano’s sixth shooting, he was placed on desk duty, but was later allowed to return to patrol. The deputies were cleared by the county district attorney’s office of any wrongdoing in the Oliva shooting.

But the movement is in it for the long haul, Cullors-Brignac said.

“The first thing this country needs to admit is it has a long history of allowing racism and classism to formulate ideas of how police officers relate to the communities they serve,” she said. “The first thing is, let’s just admit that’s happening. It’s a national crisis.”

Police violence, particularly against poor, black and brown communities in the streets of the Los Angeles region and beyond has long prevailed. But where it once remained hidden from people outside those communities, the presence of social media, the proliferation of cell phones with cameras and surveillance cameras means such violence is suddenly impossible not to see.

“When I came on the job in the late ’80s before [the Rodney King incident], it was still common practice that you had to beat the suspect after the termination of a pursuit, because you had to teach them a little bit of street justice, to teach them not to run away from the police,” said Alex Salazar, a former Los Angeles Police Department officer who now works as a private investigator for victims of police violence and helps cops with post-traumatic stress syndrome. “Obviously, Rodney King changed all that because for the first time in history, people who already knew what was going on, that they were getting assaulted and dehumanized and criminalized, had video evidence to prove it.”

“With camera phones, you can’t hide this,” Salazar said. “These officers [involved in violent incidents] will often embellish, lie. But the camera doesn’t lie.”

A testament to the power of technology may be the death of David Sal Silva, who died while being beaten even as he was restrained by Kern County Sheriffs. Deputies detained witnesses and confiscated their phones. When the devices were returned, video footage had been deleted. Deputies were afraid of what the video would reveal to the public, Salazar believes.

“They have an us-versus-them mentality. This is worldwide; this is everywhere. We’re looking at a future revolution here if they don’t do something here now.”

Salazar said a lot of officers are suffering from mental illnesses like post-traumatic stress disorder, and more still are being recruited to police departments upon returning from military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Coupled with a post-military, colonialist mindset, there is a pre-existing “cowboy culture” and code of silence that perpetuates violence.

As the problems related to that culture go unaddressed, they multiply and become less discerning. The violence is not limited to poor communities of color as it used to be, Salazar said. He pointed to the case of Zac Champommier, a white, middle-class, unarmed 18-year-old who was shot and killed by officers in a DEA task force in a parking lot in 2010.

“Cops need to be social services-oriented. Right now, they’re being taught they’re a military – robo-cop types,” Salazar said. “They have an us-versus-them mentality. This is worldwide; this is everywhere. We’re looking at a future revolution here if they don’t do something here now.”

It’s activists like Cullors-Brignac with C2ESV and the Youth Justice Coalition that are initiating those steps.

“The community is tired. We are exhausted at being beaten, at being murdered,” she said. “When we stand outside the jails and we tell people what we are doing, they say ‘finally. Finally a group of people are working to solely look at this issue . . .’ We’ve become the de facto civilian oversight and that’s not going to work for long. The community is waiting for other community members to say enough is enough.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.