Dukeville, North Carolina — Deborah Graham’s life changed on April 18, 2015, with the arrival of a letter.

Graham was in the kitchen, pouring a cup of coffee. Her husband, Marcelle, opened a large certified envelope just dropped off by the mail carrier.

“The North Carolina Division of Public Health recommends that your well water not be used for drinking and cooking,” the letter said.

“What did you just say?” Graham asked, incredulous.

“The water’s contaminated,” her husband replied.

Graham’s eyes flew to her kitchen faucet. She thought about the coffee she’d just swallowed. The food she’d cooked and sent over to her church. The two children she’d raised in this house.

She dumped the rest of her coffee down the sink.

The ordinary routines of the Graham household had been disrupted by vanadium, which can cause nausea, diarrhea and cramps. In animal studies, vanadium has caused decreased red blood cell counts, elevated blood pressure and neurological effects.

While the element is found in Earth’s crust, it’s also one of several metals found in coal ash — the toxic leftover waste from burning coal.

State officials had discovered vanadium in the Graham’s well water at an estimated concentration of 14 parts per billion, more than 45 times the state screening level of 0.3 ppb — a threshold set by health officials to warn well owners of potential risks.

And the Grahams weren’t alone. Laboratory tests showed 74 wells in the tiny Dukeville community in Salisbury, North Carolina, exceeded state or federal thresholds. Across the state, 424 households received similar do-not-drink notifications, Department of Environmental Quality Assistant Secretary Tom Reeder said in January.

Most letters cited either vanadium or hexavalent chromium, the chemical compound made famous by activist Erin Brockovich, who discovered it had tainted water in Hinkley, California. Hexavalent chromium is carcinogenic when inhaled or swallowed in drinking water, and another metal often found in coal ash.

Now, a year after they began receiving letters, many Dukeville residents are still living in a state of distrust and apprehension.

The Grahams haven’t been drinking or cooking with their water. A church in the community suspended baptisms. Others wonder what role drinking well water may have played in their illnesses over the years. And no one knows when coal ash will be removed from their community.

“We want to be able to look at our water and not fear turning on the faucet,” Graham said.

Duke Denial

State officials discovered the contamination when they tested wells close to coal ash pits, which are often-unlined ponds where electric utilities store the waste products of burning coal. Coal ash can contain radioactive elements and heavy metals, and there are more than a thousand of the pits scattered across the country.

Duke Energy and its subsidiaries are responsible for 32 coal ash pits in North Carolina, including three in Dukeville near the Graham home.

The company has been supplying affected residents with bottled water in order, it says, to offer neighbors peace of mind. But Duke has denied responsibility for polluting wells in Dukeville, saying the contaminants are naturally occurring. Meanwhile, state officials have offered conflicting messages about the safety of well water.

The community’s suspicions are fueled by Duke Energy’s record on coal ash — and state officials’ ties to the company.

Duke Energy, the nation’s largest electric utility, pleaded guilty in May 2015 to criminal violations of the Clean Water Act for spilling coal ash pollutants into waterways, and agreed to pay a $68 million fine. But months later, the company’s pits collectively were leaking about 3 million gallons of wastewater each day.

Many high-ranking state officials have had close relationships to Duke Energy, including North Carolina’s governor, Pat McCrory, who worked for the company for nearly three decades.

Deborah Graham has amassed a large collection of news clippings about coal ash and handwritten notes on her conversations with officials. (Credit: Sara Peach)

Deborah Graham has amassed a large collection of news clippings about coal ash and handwritten notes on her conversations with officials. (Credit: Sara Peach)

There’s no definitive link between the three Dukeville pits and well-water contamination. And state officials also discovered contamination at wells far from Duke’s plants. But that hasn’t calmed residents.

It Started With a Spill

Dukeville is a hamlet on the banks of the Yadkin River, 50 miles northeast of Duke Energy’s headquarters in Charlotte.

The community traces its origins to 1926, when the Buck Steam station — a coal plant named for Duke Energy co-founder James Buchanan “Buck” Duke — was constructed.

The company built many of the homes in the community as housing for plant workers and their families. It was into one of those homes, on Dukeville Road, that the Grahams moved in 1987.

Deborah Graham remembers the move as a time of excitement. She was seven months pregnant with her first child, and the community was a safe, quiet place disrupted only by the sound of church bells.

In Dukeville, “nobody bothers anybody,” Marcelle Graham said.

Deborah Graham, a talkative woman with long, straight hair and a round face, would wave to coal plant workers as they drove by. Her days were consumed by working, making sure her kids did their homework, and taking them to band and baseball practice. She didn’t know much about coal ash or worry about Duke Energy keeping a pond full of it less than 1,500 feet from her property.

Then, in February 2014, as much as 39,000 tons of coal ash spilled from a broken storm pipe into the Dan River near Eden, North Carolina, sparking renewed attention to coal ash pits near drinking water sources.

In May that year, a neighbor urged Deborah and Marcelle to attend a community meeting on the issue. Graham sat in the second row.

“I don’t understand,” she said at the meeting. “If Duke Energy wants to be a good neighbor, why don’t they just test our water?”

At the end of the meeting, she says, Duke Energy District Manager Randy Welch approached her about doing just that.

Soon, workers collected a sample from the Graham’s well for a so-called “split test,” in which the state and Duke Energy conducted independent tests of the water. In June, Welch appeared at their home, reassuring Graham the tests had found nothing of concern.

But as Graham would later learn, the tests didn’t check for vanadium.

Reached by phone, Welch declined to answer questions about his interactions with the Grahams.

Duke spokeswoman Erin Culbert said her company did not test the Graham’s water for vanadium because the state did not require it in well testing at the time of the first sampling.

But for months after the tests, Graham knew none of that. She felt secure: Her water was good to go.

Conflicting reports, cancelled baptisms

Workers at the Buck plant first began disposing of coal ash in Dukeville nearly 60 years ago. They kept adding coal ash to the pits until 2013, when Duke retired its coal-burning facility in favor of a new plant that uses natural gas.

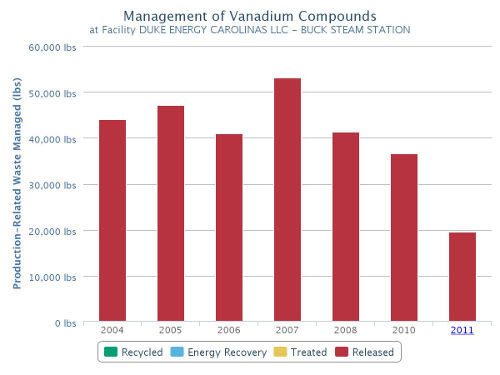

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the Buck Steam Station released 262,574 pounds of vanadium compounds and 169,018 pounds of chromium compounds total (to air, water and land) between 2004 and 2010.

In lengthy technical reports submitted to regulators, Duke Energy has said groundwater at the Buck site is flowing away from drinking wells.

(Credit: EPA)

(Credit: EPA)

But in a report commissioned by the Southern Environmental Law Center, a nonprofit that has sued Duke Energy over coal ash, two hydrogeologists called the company’s assessment of the Buck coal ash impoundments “simplistic, incomplete, and inadequate.”

The authors, Richard Spruill and Steven Campbell, are both licensed geologists and professors at East Carolina University.

Duke’s model of how groundwater flows near the ponds, they wrote, fails to account for local well-water pumping, which speeds the flow of water toward wells. Pumping can even reverse the flow of groundwater, causing contaminants from coal ash pits to migrate in ways they would not under natural conditions, the report says.

“Duke’s failure to consider, evaluate, and incorporate the effects of pumping by dozens of supply wells on the groundwater system is a fundamental flaw,” they wrote.

State officials also found Duke’s reports inadequate.

Speaking in early April, Reeder of the DEQ said Duke’s reports contain major deficiencies. “What they’ve submitted to date has not been acceptable to us,” he said.

Culbert said her company has provided all of the information requested by the state.

Duke Energy’s technical reports matter because regulators are using them to rate how hazardous each dump site is and how quickly it should be cleaned up. According to a draft report obtained by the Southern Environmental Law Center, regulators initially designated the Dukeville pits a “high” hazard, meaning the state could require cleanup of the site before 2019.

But on December 31, 2015, officials reversed course, tentatively deeming the Dukeville site a “low-intermediate” hazard, meaning cleanup might be postponed to as late as 2029. In a statement, DEQ Secretary Donald van der Vaart said the draft classifications reflected the latest science. “I am disappointed that special interest groups attempted to corrupt the process by leaking an early draft that was based on incomplete data,” he said. The state’s final classifications will be released May 18.

In the meantime, residents have spent months worrying. There’s Rev. Stanley Rice, whose congregants at Yadkin Grove Baptist Church aren’t drinking from the water fountains or cooking in the church kitchen.

“We haven’t been able to do baptismals for the sake of someone accidentally ingesting the water,” he testified at a recent public hearing.

Bonita Queen wonders if any connection exists between the drinking water and her father-in-law’s pancreatic cancer — or her own bout with thyroid cancer.

JoAnn and Ron Thomas worry about the stream of water running in a wooded gully on their property, which abuts one of the coal ash pits. Pete Harrison, a staff attorney for the Waterkeeper Alliance, said tests show the water contains high levels of coal ash contaminants. And then there’s the sense of betrayal in the community, where many people are current or former Buck plant employees. JoAnn Thomas said some of her neighbors were initially skeptical of water concerns.

“They just didn’t think that there’d be any problems, and that Duke Power would not let anything like that happen to their employees and neighbors in the community,” she said.

“How can it be OK today when it wasn’t OK yesterday?”

For Deborah Graham, responding to the issue has become a full-time job.

After she received her letter, she began educating herself about the workings of wells and state government. She amassed large piles of news clippings and documents about coal ash. Soon, she started speaking with reporters and opening her home to film crews. All the while, she filled a composition book with handwritten notes about her conversations with state officials, whose numbers she has on speed dial.

The fight has taken a toll, her husband observed recently: “She dwells on it a lot. Sometimes I know not to even talk to her, because she’s upset about it.”

But a new friendship emerged, too. A month after she got her letter, Graham attended a community meeting in Belmont, North Carolina, where Duke Energy has stored coal ash near the Allen power plant. Residents there also received do-not-drink letters from the state.

At the meeting, Graham met Belmont resident Amy Brown. The next week, the two talked by phone.

Ron Thomas and his wife, Joann, worry about the stream of water running in a wooded gully on their property, which abuts one of the coal ash pits. (Credit: Sara Peach)

Ron Thomas and his wife, Joann, worry about the stream of water running in a wooded gully on their property, which abuts one of the coal ash pits. (Credit: Sara Peach)

“Deborah,” Brown said in that first phone call, “How am I ever going to remember all this information I need to know?”

“Don’t worry,” Graham replied. “You’ll get it in like three weeks. I’ll help you.”

Soon, the two women were speaking by phone daily to share information and practice speeches.

Brown said she’s witnessed Graham’s transformation into a powerhouse activist.

“I’ve seen someone blossom into someone so amazing and fearless,” she said.

Then, in March 2016, came the surprise that would push residents’ fears into high gear.

A reporter called Graham and told her North Carolina officials were rescinding the do-not-drink warnings for wells near coal-ash pits. The water, officials said, was safe to drink.

“How can it be OK today when it wasn’t OK yesterday?” Graham asked.

When she finished her call, her phone rang again, and then again, as others from across the state reacted to the news. She tried calling Brown, but her friend’s phone was also besieged with calls. “It was like chaos,” Graham said.

Soon, residents received letters, signed by State Health Director Randall Williams and DEQ Assistant Secretary Tom Reeder, saying their water was just as safe for drinking and cooking as public water supplies regulated by the federal government.

“After further studying the issue, and learning how other cities and states handle these elements in drinking water, we believe this water is consistent with other public and well water throughout the United States and North Carolina that is either regulated or recommended to be safe,” Williams said in a statement.

In fact, EPA data suggest that vanadium and hexavalent chromium are typically present in major municipal water systems in North Carolina at lower concentrations than in many Dukeville wells.

In an interview, Williams said that North Carolina’s screening levels for vanadium and hexavalent chromium were stricter than levels set by the other 49 U.S. states and the federal government.

North Carolina’s standard for vanadium, 0.3 parts per billion, is the strictest in the Southeast, though most states in the region don’t regulate it. In California, the standard is 50 ppb.

Riccardo Crebelli, a researcher at the Italian National Health Institute who has studied vanadium in drinking water, said Italy’s standard is 140 ppb. He added that consuming the element in even higher doses hasn’t been associated with adverse effects.

“You’re drinking a carcinogen”

In 2014, California became the first state to set a regulatory standard for hexavalent chromium: 10 parts per billion. The state previously set a “public health goal” — an ideal minimum to protect health — of 0.02 ppb. North Carolina’s screening level for hexavalent chromium, which prompted letters to well owners, is 0.07 ppb.

Elaine Khan, a senior toxicologist for the state of California, said California’s public health goal was based on a one-in-a-million lifetime risk of developing cancer from consuming hexavalent chromium. “It’s as low as we can get without going down to zero,” she said.

In North Carolina, state toxicologists and epidemiologists also used a one-in-a-million risk of developing cancer to set the screening level for hexavalent chromium.

Max Costa, a professor of environmental medicine at the NYU School of Medicine, said the strict screening level for hexavalent chromium is a good one. “That’s low enough that it’s not going to cause any harm,” he said.

In Dukeville, at least 63 wells exceeded the 0.07 ppb screening level, including one where hexavalent chromium measured 21 ppb.

Costa said levels that high were cause for concern. “I wouldn’t want to drink water with 21 parts per billion hexavalent chromium,” he said. “You’re drinking a carcinogen.”

Kenneth Rudo, a North Carolina state toxicologist who endorsed the strict standard, is on leave and did not respond to a request for comment.

The Fight Continues

In the long run, Graham hopes that Dukeville residents can be connected to the municipal water system in Salisbury. But she doesn’t have much faith that state officials will protect residents.

But recently, in the hours before a public hearing on coal ash at the Buck plant, Graham showed no signs of backing down.

Outside her home, cars lined the driveway. Inside, neighbors, activists and lawyers milled in her living room. Bursting with energy, Graham introduced her guests to each other, answered her ever-ringing phone, and fretted that she hadn’t practiced her speech enough.

Soon she was on the phone with Amy Brown, who was preparing for a public hearing about the Allen plant on the same evening.

“I’ll call you tonight after the hearing,” she said. “Be strong tonight. I love you.”

“We got this,” she added.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.