One of the joys of moving to Manhattan this past spring has been the Hudson River, which flows past the front door of my apartment building. A minute’s walk takes me to a biking and walking path that goes all the way (eleven miles south) to Manhattan’s southernmost point, Battery Park. A richly diverse crowd of picnickers, joggers and bikers, African American, Dominican, Asian and European American, working class and middle class, revels against a background of blue water, and in the near distance you can see the graceful sweep of the George Washington Bridge. For me this is New York City at its best. I grew up in Philadelphia but have had family and friends in New York City since my childhood, so I’ve known it well practically all my life. It has always felt like the joyous quintessence of city living, and I suspect something in me always yearned to be here as a proud resident.

But Manhattan has been undergoing striking and dismaying changes. The real estate industry started the process, driving out New York’s legendary jazz venues and small performance spaces (I’m an amateur jazz pianist and I’ve been coming to New York to hear jazz since the 1970s), then creeping into neighborhoods to obliterate their mom-and-pop stores and most of their affordable housing, turning the city increasingly into a playground for the rich. This has happened in other American cities, as well as European ones, but New York is singular. Not only is it the country’s financial capital; it’s the US’s most walkable city. With a panoply of theaters, museums and restaurants and a skyline that ranks among the world’s most splendid, it is second only to Los Angeles as a US destination for the world’s tourists.

“There is an over-arching glory and fame to New York City,” writes Evan Pritchard in his book, Native New Yorkers, “one that shines on everyone who lives there. Go to Thailand or Italy, and tell someone you live in New York, and you too are an instant celebrity.” (Pritchard’s book is about the ways the Algonquin nation shaped, and continues shaping, Manhattan. In their general ignorance of that history, all New Yorkers are just as much usurpers of an older commonwealth as today’s super rich.)

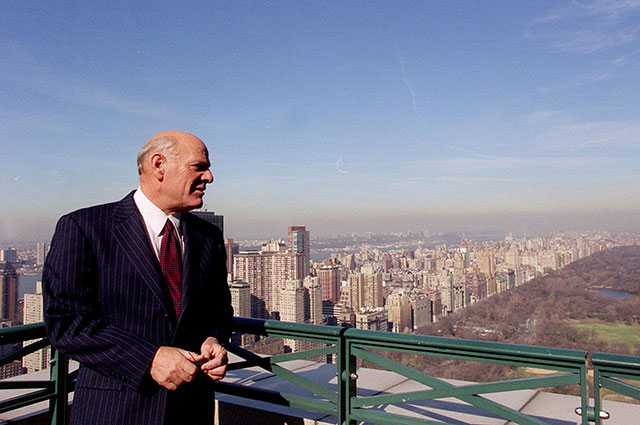

Few of the moneyed people who are changing the face of Manhattan are richer than billionaire Barry Diller, currently chairman and senior executive of IAC/InterActiveCorp and Expedia, Inc. and the media executive responsible for the creation of Fox Broadcasting Company and USA Broadcasting. Diller and his wife, fashion designer Diane Von Furstenberg, are the largest private benefactors of New York’s High Line, an aerial greenway at 20th Street built on an elevated section of a disused railway.

Since 2012 Diller has treasured the notion of building an island dedicated to himself in the Hudson, seven city blocks below the High Line. “Diller Island,” as many who know about this giant tribute to one rich man’s ego call it, is now under construction. It will consist of a long esplanade connected to a floating island with undulating greenery replete with walkways and three performance spaces, resting on 300 piles that in pictures look like so many golf tees. The whole structure will reach elevations as high as 70 feet. At 2.4 acres it will be larger than two football fields, jutting out from the shoreline like a cluster of enormous mushrooms. It is backed by glitterati who include Governor Andrew Cuomo, Mayor Bill de Blasio and Diana Taylor, chair of the board of directors of the Hudson River Park Trust (HRPT) and companion to former Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

The land where the island is to be built is public. It falls under the jurisdiction of the HRPT, a partnership between New York State and City charged with the construction and design of the four-mile Hudson River Park. The Park belongs to millions of New York City residents whose taxes subsidize it. And so it’s significant that Diller Island’s backers include de Blasio, who in 2014 chaired a “Cities of Opportunity Task Force” and whose pledge to create a more equal city hallmarked his third State of the City address last February, even while his increasing partnerships with the very rich in beefing up social programs has drawn media attention.

Diller Island, though, isn’t like the existing public programs de Blasio has promised to bolster (schools, more broadband access for the Bronx, affordable housing, etc.). It’s an almost wholly private venture dedicated to a single person and largely financed by him. In this venture, the responsibilities of regulatory agencies have been eroded. They include the US Army Corps of Engineers and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, both of which this past spring gave permits for the giant structure despite the fact that its promoters have never filed a state-required environmental impact assessment. If the project succeeds, it will be one of the nation’s leading precedents for the colonization of public spaces by private interests.

Charged with all construction in the park, the HRPT is responsible for endorsing and forwarding the project. In January 2015 The City Club of New York, a land-use policy organization, together with other groups launched a lawsuit against the Trust to halt the project. The suit charges that the Trust has never carried out the requisite environmental impact review; that the agreement to build the island was kept secret until it was announced in 2014; that its performances would be largely unaffordable for New York’s citizens; and that it would obstruct the view for which the esplanade running along the Hudson is famous. The Trust’s representatives claim that it has engaged in its own ecological reviews, and that the island will simply enhance a shoreline that had been falling into ruin. Madelyn Wils, who began her tenure as the Trust’s CEO in 2011, in 2015 asserted that the Trust was taking care of the river. “We take our role as stewards of the Hudson River Park sanctuary seriously,” she told The New York Times. “And that’s exactly why we not only conducted a thorough environmental review in accordance with state law, but went beyond what was required by inviting public comment on that review.”

But The City Club’s president, Michael Gruen, charges that a proper environmental impact statement (EIS), as required by New York’s State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA), has never been filed by the Trust. Neither has The Army Corps of Engineers filed a similar EIS required at the federal level. “Instead,” Gruen told me, “they did what is called ‘a negative declaration,’ which says they considered the possible impacts and decided there was no possible adverse impact.”

Gruen added: “Bypassing the EIS requirement and the extensive public input it would have required, [the Trust] decided on its own, and with its own bias in favor of the project, that there is no possible adverse impact worthy of further analysis. SEQRA presumes that a project of this magnitude must get the thorough investigation of an EIS to assess the presence and extent of adverse impacts. Clearly there are … possible impacts, such as the obliteration of a two-block wide view over the Hudson from the shore, that cannot be dismissed with the wave of a hand.”

The City Club is suing the Trust in Manhattan Supreme Court. In late June a New York State appeals court ordered work temporarily halted on the project. But in July the judicial panel modified the order, allowing some piles to be installed. In early September a New York State appellate court ruled that construction could proceed. The City Club is appealing the decision.

A curious aspect of the story is that it involves two of the super-rich squaring off against each other. A real estate tycoon, Douglas Durst, once chairman of the Trust, is supporting the suit. Durst hasn’t disclosed whether he is financing it, but he has said, “I do not like the process or the project and I am in favor of the litigation.” Mr. Durst could not be reached for comment for this article.

Public parks are notoriously expensive to run, and Hudson River Park is no exception. Founded in 1998, it extends from 59th Street south to Battery Park. Originally it was to be funded mainly by capital from the State and City, but in an era of municipal and state financial scarcity, the Trust has depended on donations. In early 2012 Madelyn Wils approached Diller for a contribution to repair a long-dilapidated pier on the river at 13th Street, Pier 54, where survivors of the Titanic’s iceberg collision landed in 1912, and from where the Lusitania departed on its fateful voyage in 1915 (it was sunk by a German submarine). Discussions about what to do with the long-derelict structure had swirled around Pier 54 from the early 1990s. But instead of writing a check specifically designated for its repair, Diller proposed a brand-new park that would be called Pier 55. He donated $113 million for constructing it, promising to fund its maintenance for 20 years. The full cost will be $170 million. The public will foot $39.5 million, a little over a fifth of the cost but hardly chicken feed.

While the HRPT billed Pier 55 as a reconstruction of Pier 54 it turned out, says Gruen, “that the Trust had been talking with Mr. Diller for several years … and had worked out a plan that was completely different.” Diller Island will be far larger, and built outside the original Pier 54 limits. The act that originally established the park stipulated that no construction could take place other than reconstruction of existing piers in their original form and in their footprints. But in 2013 the act was amended to allow certain other structures to exist outside those parameters.

A Fish Story

The legislation that created Hudson River Park empowered the Trust to design, build and operate it, designating its 400 water acres as an estuarine sanctuary, “a critical habitat worthy of special protection,” to be cared for by the Trust “in a manner which promotes and preserves the Sanctuary’s marine resources.” (An estuary is the lower part of a river where salt water from the ocean meets fresh water from the land.)

One of the Hudson’s stellar resources is its legendary striped bass population, which in its first year of life spends the winter in the waters surrounding Pier 54. The bass have been under threat before. In the 1980s an estimated $2.4 billion mega project called Westway would have run a four-mile-long super highway into the river on landfill, obliterating the bass’s habitat.

This massive undertaking was backed by Presidents Carter and Reagan, Governors Hugh Carey and Mario Cuomo, Senators Alfonse D’Amato and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Mayor Edward Koch, David Rockefeller and The New York Times, among others. Memorialized in numerous books and articles, Westway was fiercely opposed by a mass movement involving a coalition of organizations that included the Sierra Club, the Clean Air Campaign and The Hudson River Fishermen’s Association, founded in 1966 by Robert Boyle, an environmentalist/journalist who for 40 years wrote articles about angling and other topics for “Sports Illustrated,” and participated in all of New York’s major environmental battles starting in the early 1960s. Because of the strength of the coalition and in specific because of the participation of the Fishermen’s Association, Westway was defeated. The judicial ruling halting the project cited the harm it would have caused to the striped bass.

Westway’s proponents engaged in chicaneries that included a false tally of the river’s striped bass population by the Army Corps of Engineers, involved here, as it is in the Diller Island project, because it is responsible for regulating activities that could obstruct or alter navigable US waters. “I have sentenced people to prison for securities fraud where the conduct was less blatant than the drafting of these instruments [the fallacious striped bass studies]. I am deadly serious about this,” said Thomas P. Griesa, federal judge for the southern district of New York, in ruling against the project.

“Given the bitter and prolonged battle over Westway, laden with deceit by its backers, any proposed change in the area is automatically suspect,” says Boyle.

Who Will Protect the River?

Riverkeeper, the organization that succeeded The Hudson River Fishermen’s Association and gave rise to 150 similar river protection organizations worldwide, at its website describes its mission as “defending the Hudson River and its tributaries.” In January 2015 its then-program director, Phillip Musegaas, together with NY/NJ Baykeeper Executive Director Deborah A. Mans, wrote a meticulously documented 13-page letter that reads like a legal brief, to William Heinzen, senior vice president and legal counsel for the Trust. Salient points include charges that the Trust hadn’t provided a proper EIS and that its deliberations over the new structure were conducted “entirely behind closed doors.” The letter projected “myriad significant environmental impacts that are likely to result from the construction and operation of Pier 55, including loss of river habitat in the Estuarine Sanctuary from dredging and pile driving, long-term impacts from shading caused by the pier … impacts of lighting on river habitat, as well as noise, traffic and visual impacts to the Hudson River, adjoining areas of the Park and nearby New York City neighborhoods.”

Despite this textbook summary of the myriad cases against the project, Riverkeeper has failed to join the City Club suit. My calls to Riverkeeper’s president, Paul Gallay, weren’t answered. Instead, the group sent a letter abdicating Riverkeeper’s responsibility on the basis that other parties were suing the Trust. When asked for comment about the letter, Phillip Musegaas, now legal director at Potomac Riverkeeper, said: “The letter speaks for itself. It was the position of the organization at that time. I no longer work for Riverkeeper, so I don’t have anything to add.”

“I find it astonishing,” says Peter Silverstein, a former member of the board of directors of the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association, “that Riverkeeper has failed to take action against this project. This is even more surprising in light of the fact that Riverkeeper sent detailed comments outlining the potential impacts of this project to the Hudson River Park Trust in January 2015.”

In an email to me last month, fishing historian and Hudson River advocate John Mylod lambasted the “corrupt political system of conflicts of interest, campaign contributions, compliant permitting agencies and neutered environmental groups [that] make this kind of environmental fiasco possible.” Put another way, Diller Island is a grand illustration of “money talks,” showing the impacts America’s new, unrestrained gilded age can wield on the property of U.S. citizens.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $34,000 in the next 72 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.