Nineteen states are asking a federal court in California to block new Trump administration regulations that would end a longstanding legal agreement requiring minimum standards of the care for migrant children in federal custody and reinstate the indefinite detention of migrant families.

In a press conference Monday, Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson pointed to interviews conducted by state civil rights investigators with 28 migrant children ages 12 to 17 who were transferred to state-run childcare facilities in Washington after being held at federal detention sites (in effect, migrant jails) at the southern border sometime over the past year. The interviewees described conditions in the migrant jails: cramped cells, young kids locked in metal cages for days as punishment and guards throwing food on the floor for children to fight over.

The migrant teens also reported lack of access to basic sanitary supplies, such as soap, toothbrushes, tampons and pads, all problems that were previously reported in the media. A federal court has since ordered the Trump administration to provide basic hygiene products to migrant children incarcerated at the border under a decades-old consent decree known as the Flores settlement. With the new Trump regulations, federal officials are now seeking to “terminate” the Flores settlement, which would allow for the indefinite detention of migrant parents and their children.

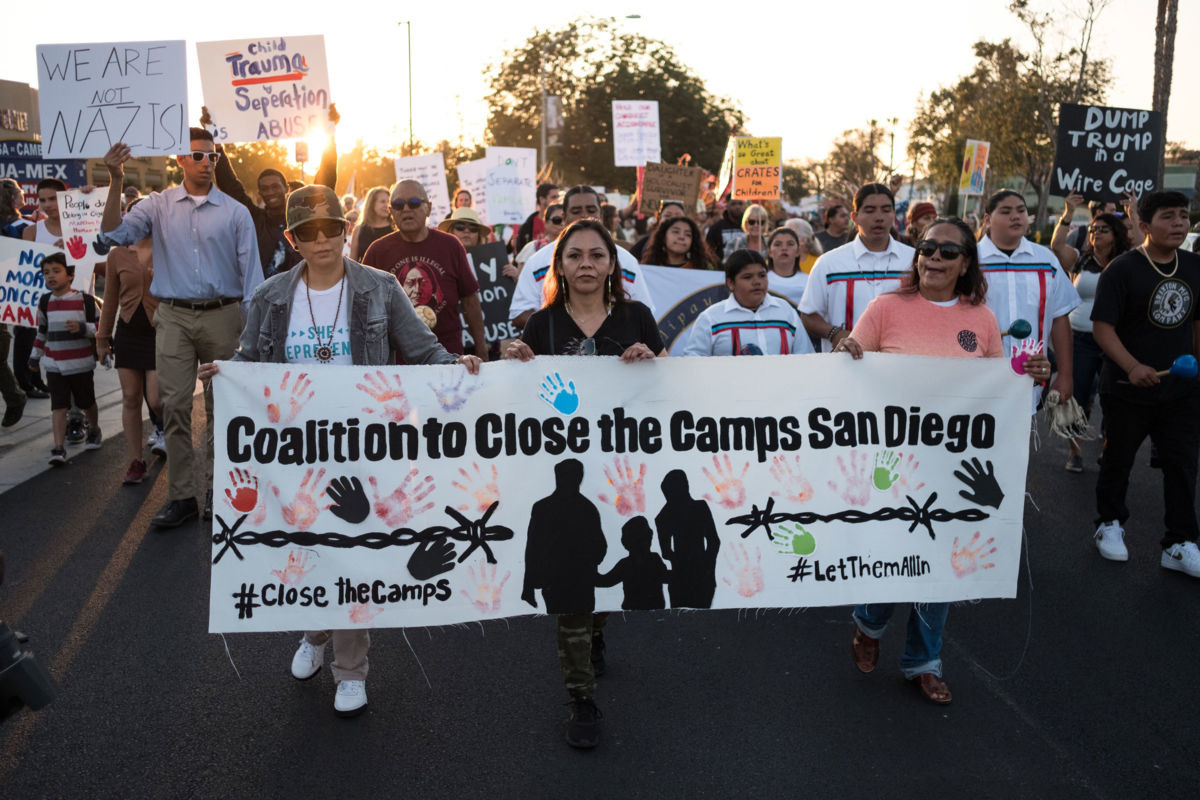

A coalition of Democratic attorneys general lead by Ferguson, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra and Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey filed a lawsuit on Monday challenging the administration’s plan to detain families together for longer periods of time. Thousands of migrant children are released from detention into Washington, California and other states every year, they argue, and many will carry the psychological trauma caused by incarceration with them.

“Detaining families indefinitely and needlessly inflicting trauma on young children is not an immigration policy — it’s an abhorrent abuse of power,” Washington Gov. Jay Inslee said in a statement.

Ferguson said he plans to file the interviews with migrant teens with the federal court in California. After being held by federal law enforcement near the border, the teens were transferred to state-licensed facilities in Washington, where group homes and “secure facilities” contract with the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refugee resettlement program to provide up to 100 beds for unaccompanied minors, according to Ferguson’s team. Under the Flores settlement, migrant children who are apprehended can only be detained for up to three weeks before being released to HHS, which generally places them with relatives or in state-licensed facilities or foster care.

This time limit for incarcerating children has frustrated the Trump administration, which reversed its family separation policy of jailing undocumented parents after a federal judge ordered officials to reunite families last year.

Now, as officials work to rapidly expand incarceration for undocumented immigrants, the Trump administration wants to jail migrant children with their parents indefinitely as they wait for a judge to hear their immigration cases. With new regulations unveiled last week, the administration aims to “implement” new standards for detaining migrant families indefinitely in specialized jails and other facilities that officials say would satisfy Flores and render the settlement obsolete. The rules would also codify how HHS “accepts and cares” for unaccompanied children.

Ferguson said the Trump administration would be able to “suspend” these standards if an “influx” of migrants arrived at the southern border, and the administration’s definition of influx is so broad that many instances of increased immigration over the past several years could have triggered the suspension of these “minimal” detention standards, had the Trump regulations been in place.

Ferguson and other opponents say the widely reported mistreatment of children at federal border detention sites is proof that the administration cannot be left to regulate itself. The new regulations for indefinite detention, they argue, would prevent state oversight of immigrant detention by striping states of their role in regulating the minimum standards for facilities that house migrant children for the federal government.

“States have a well-established role in licensing facilities and foster families that house immigrant children for the federal government,” Ferguson told reporters on Monday. “The rules cut out states entirely.”

Currently, Washington and other states provide licenses to facilities that contract with HHS to care for unaccompanied migrant children based on standards applied to teachers and child care providers. The administration’s regulations, opponents say, would allow Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to place migrants in unlicensed facilities that are instead evaluated by “third-party” inspectors hired by ICE.

Ferguson, a Democrat who has filed 47 lawsuits against the Trump administration, said the new rules would prevent state officials like him from conducting oversight of family detention facilities and facilities for unaccompanied children in their state. The teenagers his team interviewed made it clear that Trump administration’s incarceration-focused policies are traumatizing children, who may be in need of mental health support once they arrive in a state such as Washington, he said.

“If the new rules were in place … the state, my office and our partners would be unable to share these stories because we would no longer have state oversight over these children,” Ferguson said, referring to the 28 migrant teens interviewed by state investigators.

Currently, there are no family detention facilities in Washington and several other states joining in the lawsuit, although Ferguson’s aides said there is a possibility the federal government could try to build more. If the administration is able to reinstate the indefinite detention of families, most would likely be held at two large facilities in Texas where families were held indefinitely in 2014 and 2015 under the Obama administration, unless Congress authorized funding for more.

In a press conference last week, Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Kevin K. McAleenan said the facilities for detaining families are “fundamentally different” from those where migrants are held after being apprehended at the border. They are “campus-like settings” with “appropriate” medical, educational, recreational and nutrition services, he said. However, families would be locked in the facilities until they are either deported, granted asylum or released on bond.

McAleenan said detaining families would allow the government to speed up deportation proceedings, allowing asylum seekers to have their cases processed faster. He claimed that indefinite incarceration would also act as a deterrent to migrants and smugglers who believe that arriving at the border with children is a “free ticket into the country.” Under the Obama administration, the average family was detained about 50 days, he said.

However, migrants could potentially be detained much longer, with no guarantee that their asylum claims will be accepted by a judge. During the Obama administration, the indefinite detention of migrant families became a flash point of controversy, and one family-holding center was shut down amid complaints of poor conditions. The administration’s border holding pens and its existing immigration jails for adults are already under fire for poor conditions, accessibility problems and medical neglect.

Ferguson’s lawsuit asks a federal court in California — the same court that devised the Flores settlement — to issue an injunction that would block the Trump administration’s regulations for indefinite family detention. If the judge agrees, indefinite family detentions could be put on hold for months as the case winds through the courts.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.