Click here to open in a new window, then again to view full-size.

Click here to open in a new window, then again to view full-size.

Click here to open in a new window, then again to view full-size.

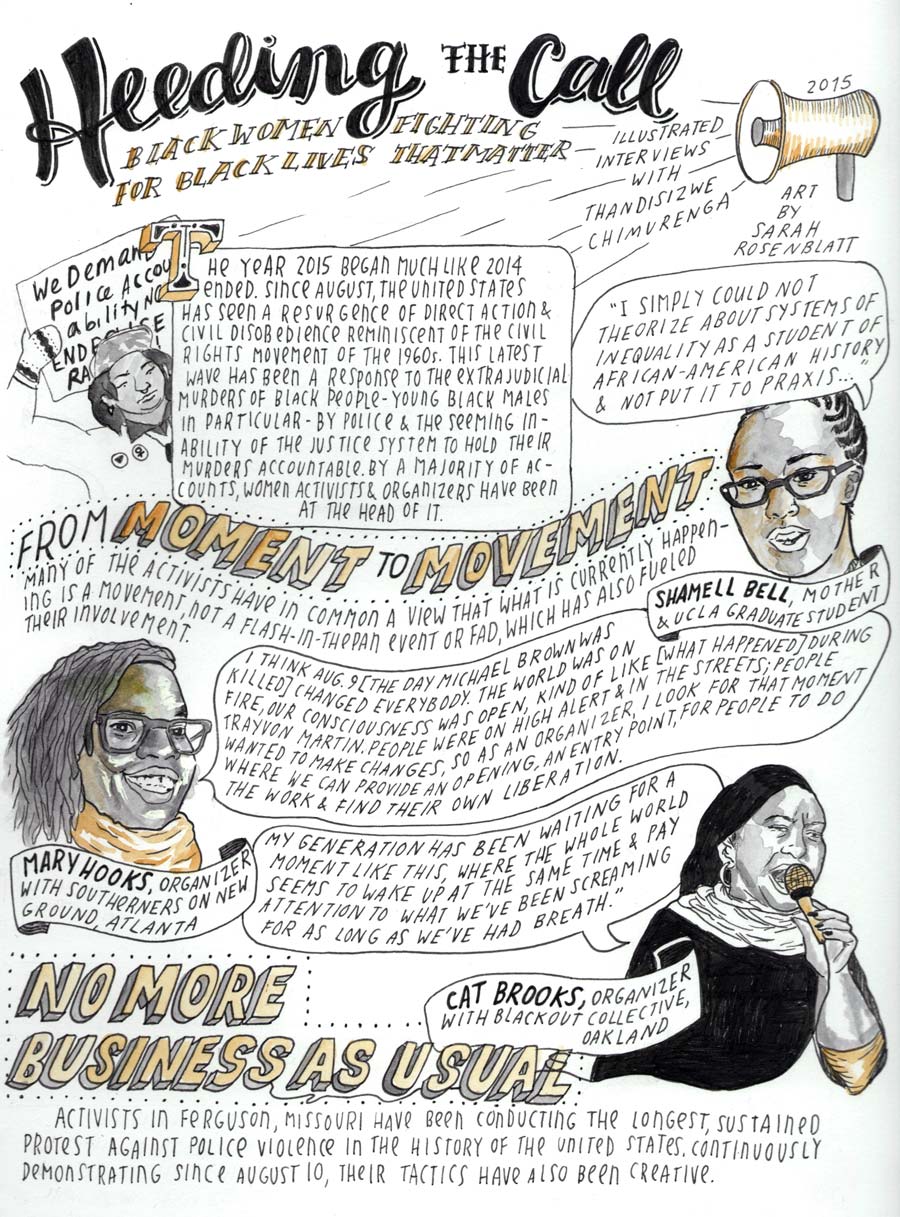

The year 2015 began much like 2014 ended. Since August, the United States has seen a resurgence of direct action and civil disobedience reminiscent of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. This latest wave has been a response to the extrajudicial murders of Black people by police – young Black males in particular – and the seeming inability of the justice system to hold their murderers accountable. And, it has been headed largely by Black women activists and organizers.

More militant and sustained than the Occupy protests of a few years ago, or the World Trade Organization protests at the latter part of the 20th century, this movement, which began in Ferguson, Missouri, and has traveled worldwide, has been as dedicated to affirming the value of Black life as it has been to condemning state-sanctioned violence against Black bodies.

While Black women are also victims of murder by police, the tally is not as high as for Black men. And, while many of their names are known and the circumstances of many of their deaths are similar to the murders of Black men, the level of outrage and protest has not been comparable. The reasons for this are varied.

“My generation has been waiting for a moment like this, where the whole word seems to wake up all at the same time.”

Black women’s motivations for intimate involvement in this movement, however, appear not to be as varied. Several activists and organizers in solidarity with Ferguson and behind Black Lives Matter protests recently expressed a similar set of motivations for their participation to Truthout. They said they became involved because they felt they “had to.”

“As a mother, I was concerned for the future of my children and my community, so I felt compelled,” said Melina Abdullah, a university professor of Pan African studies and an organizer with Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles. “I didn’t feel like it was a choice. It was a duty.”

Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson, a Chattanooga, Tennessee, organizer with Black Lives Matter, concurred. “I got involved in this movement because I felt required to fight for the lives of myself and my loved ones,” she said.

According to Cat Brooks, who works with the BlackOut Collective in West Oakland, she sees her involvement as her life’s work. “This is what I’m called to do,” she said. “I don’t know how to do anything else.”

UCLA graduate student Shamell Bell said she had a “visceral reaction” to imagining her son victimized by the same state violence and anti-Black racism that killed Eric Garner and Michael Brown. “I simply could not theorize about systems of inequality as a student of African-American history and not put it to praxis,” she said.

Jasmine Richards, a lobbyist in Pasadena, says she joined the movement to affirm the value of Black lives, but not solely because they were being victimized by police. “The reason why I felt compelled to do this work is because my friends keep dying. Black on Black violence, Brown on Black violence, they keep getting murdered, and I’m tired of putting their faces on T-shirts, or tattooing their name on me somewhere. I’m tired of it,” Richards said.

From a “Moment” to a “Movement”

Many of the people Truthout spoke with also have in common a view that what is currently happening is a movement, not a flash-in-the-pan event or a fad, which has also fueled their involvement.

“My generation has been waiting for a moment like this, where the whole word seems to wake up all at the same time and pay attention to what we’ve been screaming for as long as we’ve had breath,” said Cat Brooks.

“These state-sanctioned murders have taken place with limited impact on non-Black people, while at the same time, they are destroying Black communities.”

Mary Hooks, an organizer with Southerners on New Ground (SONG) in Atlanta agreed. “I think August 9 [the day Michael Brown was killed] changed everybody,” Hooks said. “The world was on fire; our consciousness was open; kind of like [what happened] during Trayvon Martin. People were on high alert and in the streets, people wanted to make changes; so as an organizer, I look for that moment where we can provide an opening, an entry point, for people to do the work and find their own liberation.”

“I have always said I wished I was coming of age during the civil rights movement because I wanted to be a part of change,” said Shamell Bell. Bell was a part of Justice for Trayvon Martin-Los Angeles, the predecessor to the Los Angeles chapter of Black Lives Matter. “I knew it was my chance to do work in a movement as I have always imagined was my purpose and my vision.”

“People keep narrowing it and it’s so much more,” said Jasmine Richards. “I see [Black Lives Matter] as a statement that gave life to a place that didn’t have life. It’s opening up a whole new world to a lot of us. It’s making us love each other and it makes us speak to one another: ask ‘how we’re doing?’ instead of ‘mean-mugging’ or ‘mad dogging’ one another,” Richards said.

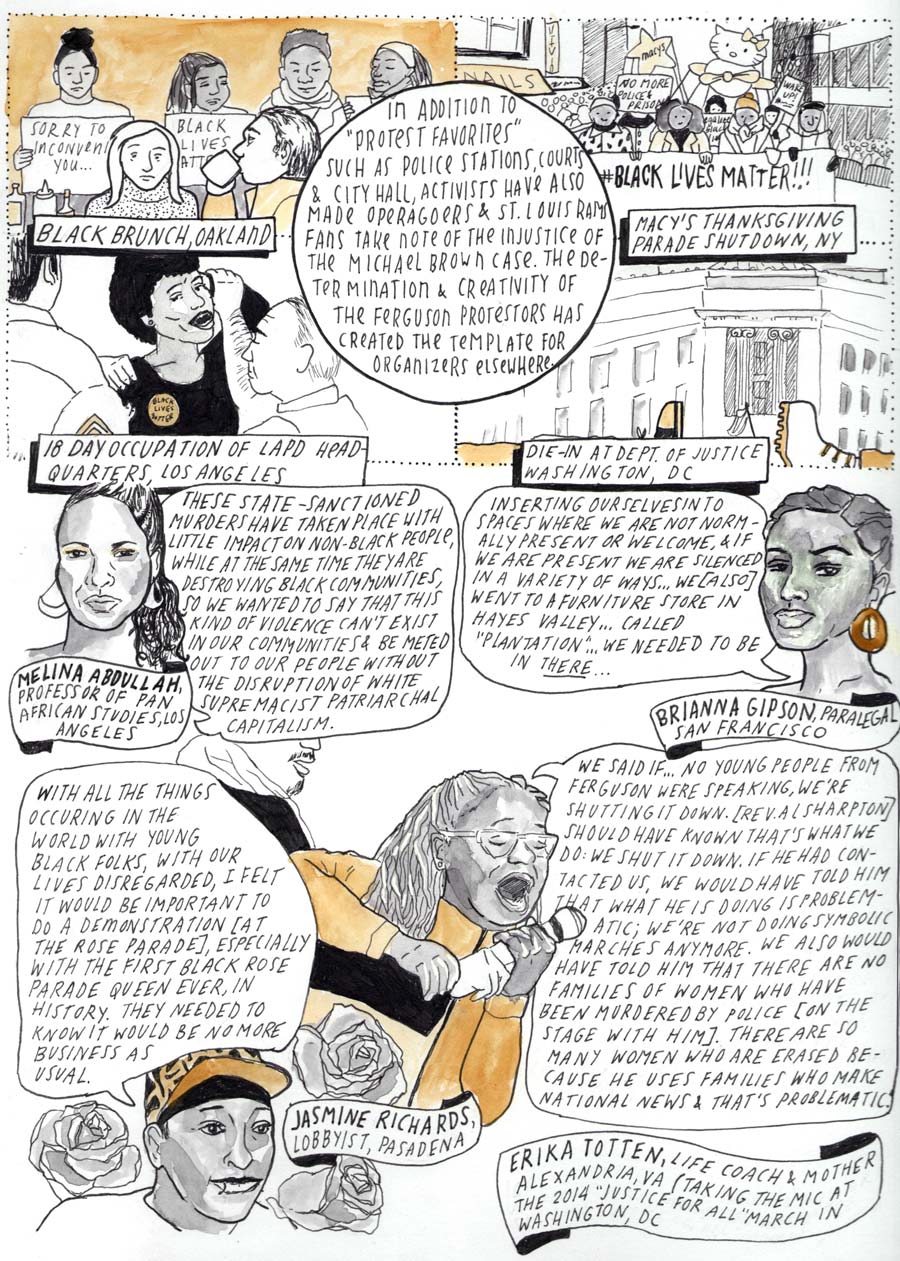

No More Business as Usual

Activists in Ferguson, Missouri, have been conducting the longest sustained protest against police violence in the history of the United States. Continuously demonstrating since August 10, 2014, their tactics have also been creative. In addition to “protest favorites,” such as police stations, courts and City Hall, activists have also made operagoers and St. Louis Rams fans take note of the injustice in the Michael Brown case. The determination and creativity of Ferguson protesters have created the template for organizers elsewhere.

In Los Angeles, Black Lives Matter’s predecessor, Justice for Trayvon Martin-Los Angeles, took their protests over the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the summer of 2013 to Beverly Hills’ glitzy and glamorous Rodeo Drive. Since the refusal of grand juries to indict Darren Wilson and Daniel Pantaleo for the murders of Brown and Garner, they’ve disrupted Christmas shoppers at The Grove on the city’s Westside, shut down a portion of the busy Hollywood Freeway and occupied the Los Angeles Police Department’s headquarters for 18 days to bring attention to the killing of another unarmed Black man, Ezell Ford, around the same time as Brown was killed in Ferguson.

“These state-sanctioned murders have taken place with limited impact on non-Black people, while at the same time, they are destroying Black communities,” said Abdullah, “so we wanted to say that this kind of violence can’t exist in our communities and be meted out to our people without the disruption of white supremacist patriarchal capitalism.”

Actions in the San Francisco Bay Area – a shut down of some Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) trains on “Black Friday,” the padlocking of the Oakland Police Department (OPD) headquarters, a “wake-up call” on the front lawn of Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and “Black Brunch” – have been organized with the same principle in mind, according to Brooks and Brianna Gipson.

“This is not your grandparents’ civil rights movement.”

“[It’s about] inserting ourselves into spaces where we are not normally present or welcome, and, if we are present, we are silenced in a variety of ways,” said Gipson, a San Francisco paralegal and organizer of “Black Brunch,” which brings the issue of state-sanctioned violence directly into eateries and cafes. “We [also] went to a furniture store in Hayes Valley … called ‘plantation’ … we needed to be in there,” Gipson said.

“BART was chosen specifically because of their role and very long history of egregious crimes against the Black community; OPD is the perpetrator of the crimes that are part of the state’s war against Black people and so why not take the resistance directly to their doorstep?” Brooks said.

“The mayor, Ms. Schaaf, has a horrific history when dealing with police terror in Oakland,” Brooks added. “From her support of the Urban Shield Conference (showcasing military grade weapons and technology), to the handling of the Alan Blueford murder, to announcing on her first day in office that the police were her most important priority – not the hungry, not the homeless, not education, not jobs – she actually told us that the police … were her most important priorities … so it became clear to us that we needed to communicate to Ms. Schaaf that actually, the people are going to be her priority while she is mayor of Oakland.”

“My family stopped going to the Rose Parade when I was about 7 or 8; we just felt there was no place for us here,” remembers Jasmine Richards. “And so with all the things occurring in the world with young black folks, with our lives disregarded, I felt it would be important to do a demonstration [there], especially with the first Black Rose Parade queen ever, in history. They needed to know it would be no more business as usual,” Richards said.

When they say there is “no more business as usual,” the activists aren’t just talking about what they feel is an indifferent (white) public.

In Erika Totten’s view, it’s also about the character of the protests themselves. That was made abundantly clear to the Rev. Al Sharpton of the National Action Network when he called for a national protest against police brutality in August in Washington, DC. Totten took to the stage during the event and physically took the microphone from the moderator, demanding that Ferguson activists, who were not on the program to speak, be given time to address the audience.

“We said if there were no young people from Ferguson [who were present in DC at the time] speaking, we’re shutting it down. He should have known that’s what we do: We shut it down,” said Totten. “If he had contacted us and talked to us, we would have told him that what he is doing is problematic; we’re not doing symbolic marches anymore.”

Totten also criticized Sharpton for what she called the erasure of Black female victims of police murder. “We also would have told him that there are no families of women who have been murdered by police [on the stage with him]. There are so many women who are erased because he uses the families that are national news and that’s problematic.”

The Washington, DC, metro area has been a prime location for protests by Totten and other activists. The Alexandria, Virginia-based spiritual life coach and stay-at-home mom and her comrades have shut down the I-395 freeway that runs through the DC-Maryland-Virginia area, the area surrounding Pentagon City and various metro rail lines; held die-ins at the Department of Justice and joined with others who called for a job walkout in the city of DC.

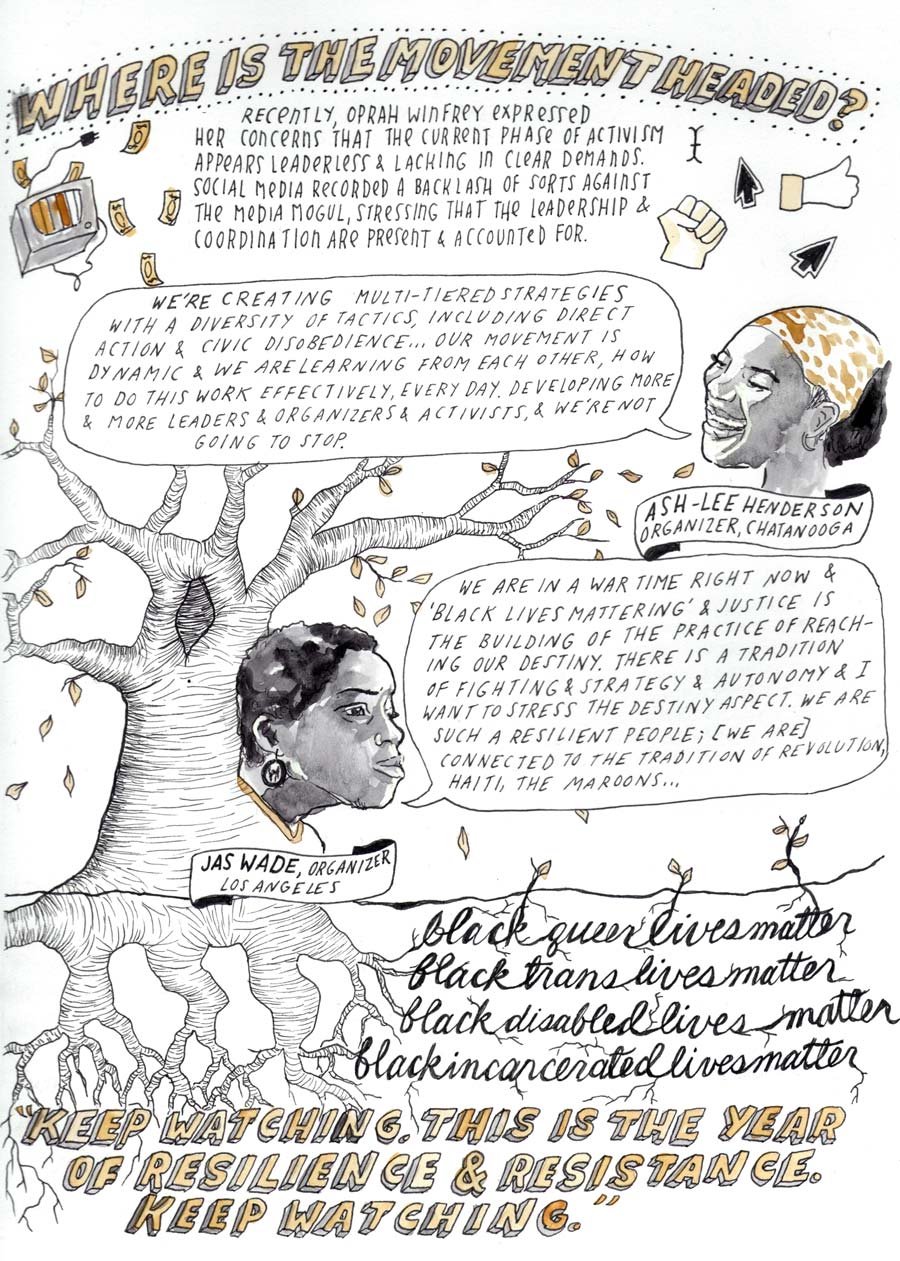

Where Is the Movement Headed?

Recently, Oprah Winfrey expressed her concerns that the current phase of activism appears to be leaderless and lacking in clear demands. Social media recorded a backlash of sorts against the media mogul, stressing that the leadership and coordination are present and accounted for, despite what Winfrey may think she has observed.

According to Ashe-Lee Henderson, “We’re creating multitiered strategies with a diversity of tactics, including direct action and civil disobedience … Our movement is dynamic and we are learning from and with each other, how to do this work effectively, every day. Developing more and more leaders and organizers and activists, and we’re not going to stop.”

As Ferguson activist and rapper Tef-Poe put it, “This is not your grandparents’ civil rights movement.”

That being the case, where do the activists and organizers in the forefront of the movement see it headed? Again, their replies were strikingly similar.

“There is a short-term and a long-term,” said Melina Abdullah. “We have to think about the ways that state-sanctioned violence against Black people is tied to a system that keeps us oppressed, so really what we are talking about is a complete transformation of the existing system.”

Cat Brooks agreed and added that the rebuilding of society must be one “where Black women men and children are clear that their history did not begin in the Middle Passage, and are fully aware of the beautiful beings that they are, and as a result of that awareness, have a deep love for themselves and their brothers and sisters.”

“We are in a wartime right now and ‘Black lives mattering’ and justice is the building of the practice of reaching our destiny,” said Jas Wade, who self-describes as “a Black gender-queer being of Afrikan descent.” “There is a tradition of fighting and strategy and autonomy and I want to stress the destiny aspect. We are such a resilient people; [We are] connected to the tradition of revolution, Haiti, the Maroons.”

For Mary Hooks, Black people being self-determining and building on a legacy of resistance and continuing to fight for justice are as important as practical concerns. “It looks like being able to have safety and dignity, me being able to raise my 2-year-old in a community where she is valued and her well-being is as important to me as it is to the people around her we pay to make sure she is safe and educated.”

Like the others, Hooks acknowledges that it will take time to fully realize the vision where “Black women, queer, trans, poor and otherwise marginalized Black folks are free to be their fullest selves in our communities and movement spaces and everywhere.” Like Melina Abdullah, she sees a short-term and a long-term. Hooks thinks that both observers and participants should be patient with the process.

“Actions may seem like they are not doing anything, but it is an opportunity for folks to contribute to this movement and bring them closer to this work, people who have never used the word ‘justice’ before,” Hooks said.

“Keep watching. This is the year of ‘resilience and resistance.’ Keep watching.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.