The 2020 Democratic presidential candidates have been nearly silent on a significant issue: Guantánamo. None of the candidates are making the still-open Guantánamo Bay prison a campaign issue. This is a huge shift from the Bush years, when liberal politicians criticized the Bush administration for the Iraq war, torture and other constitutional violations.

Throughout the first Democratic primary debate, Guantánamo was mentioned only once. During the first night, Ohio congressman Tim Ryan said, “terrorists at Guantánamo Bay” get better health care than migrant children detained in concentration camps on the southern United States border.

Describing the remaining Guantánamo detainees as “terrorists at Guantánamo Bay” gets it wrong. Most of them have not been charged nor tried for any crimes, let alone terrorism. They’re detained at Guantánamo indefinitely, which is against international human rights law. Only seven detainees are being tried at the military commissions but they have yet to be convicted of terrorism.

More importantly, Ryan’s comment repeats the false narrative that every Guantánamo detainee is a James Bond supervillain. Most of the Guantánamo detainees are not “the worst of the worst,” very few were actually al-Qaeda fighters, and some detainees had nothing to do with al-Qaeda or the Taliban. Some, like Abdul Zahir, who was released in 2017, were detained based on mistaken identity. Mark Fallon, a retired 30-year federal investigator who, from 2002 to 2004, led a Pentagon task force to investigate cases that would be brought before a military commission, previously told Truthout that “an overwhelming majority” of detainees had no intelligence or investigative value and should have been released.

Recently, Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, told CBS News that he would shut down the Guantánamo prison. He also called for “an end to endless war,” specifically a repeal for the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF). In the large pool of Democratic candidates, this sole comment is slim pickings.

The relative silence on Guantánamo stands in sharp contrast with the 2008 election, when then-candidate Barack Obama ran on a platform of opposing the Iraq war and closing down the Guantánamo prison. While Guantánamo was not a central issue in the 2016 presidential campaign, it did come up. During the 2016 Democratic primary, Bernie Sanders criticized Hillary Clinton for voting to keep Guantánamo open.

What changed? Unfortunately, Guantánamo and indefinite detention have become normalized fixtures of U.S. foreign policy.

Why Has Guantánamo Stayed Open?

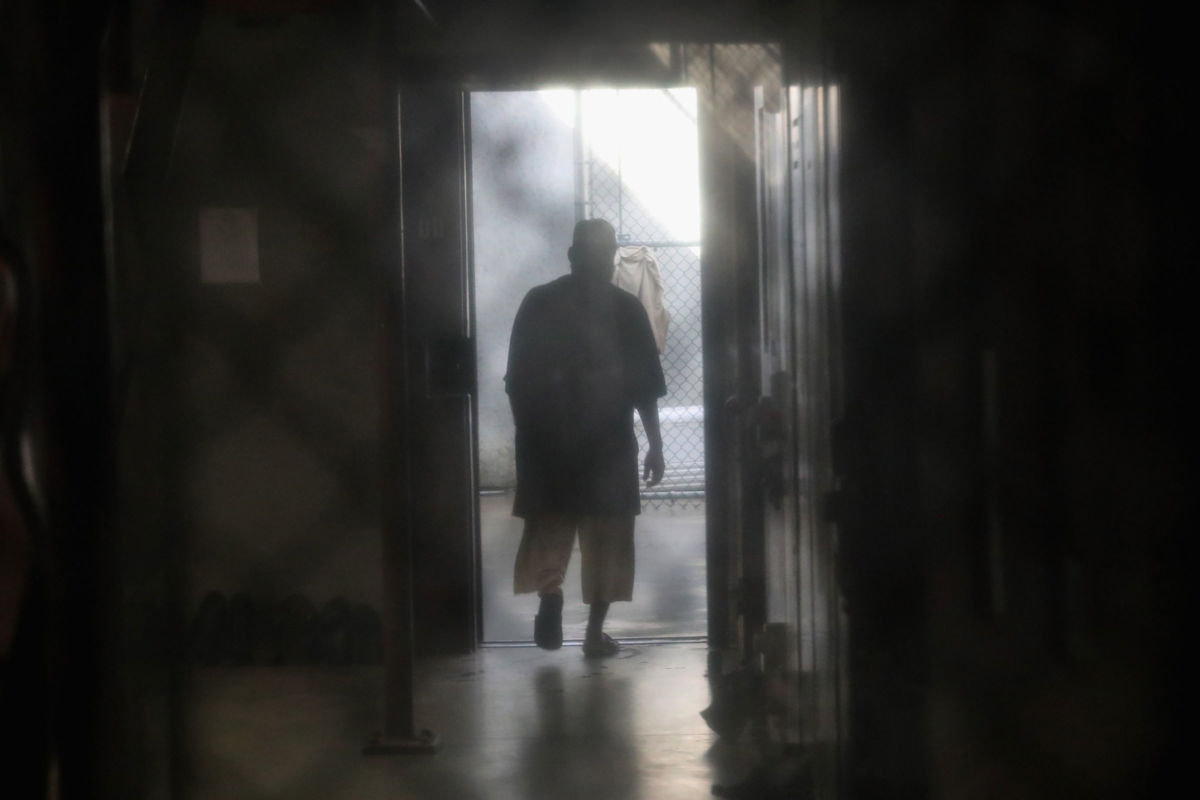

The detention facility at the U.S. naval base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, has been open and holding detainees since 2002. As of this writing, 40 detainees remain in the prison. Of those remaining detainees, 26 people are held in indefinite detention without charge or trial. Indefinite detention violates international human rights law, particularly the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which the U.S. is a signatory. Only five people are cleared for transfer.

Why is the prison still open, even though former President Obama made a campaign promise to close it down?

First of all, Obama’s plan to close Guantánamo was not to actually close the prison but, rather, to transfer Guantánamo’s system of indefinite detention to U.S. soil by moving Guantánamo detainees to a federal supermax prison. Even that false solution never came to pass; Obama continued the system of indefinite detention at the existing prison. In May 2009, Obama actually endorsed indefinite detention, saying that the U.S. should continue detaining some Guantánamo detainees without charge or trial. The U.S. government claims the indefinite detainees are ostensibly too dangerous to release and too difficult to prosecute in a civilian court because of inadmissible, and often torture-obtained, evidence.

A fundamental reason why the U.S. government continues to indefinitely detain dozens of men is because of the perpetual war powers granted to the executive branch after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The 2001 AUMF allows the president to use force against those responsible for 9/11 and other suspected terrorists around the world. The U.S. government also uses the AUMF to justify indefinite detention, though many human rights lawyers have challenged this justification. The government’s argument is that the United States is engaged in a global armed conflict against al-Qaeda and “associated forces,” which means the U.S. government has the right to detain suspected terrorists “until the end of hostilities.”

The Trump administration has echoed this argument. In 2017, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, “The 2001 AUMF … provides a domestic legal basis for our detention operations at Guantánamo Bay.”

The Obama administration coined the term “associated forces,” which means al-Qaeda’s co-belligerents, and interpreted the 2001 AUMF to cover those groups, including some, like Somalia’s al-Shabaab, that didn’t exist until after 9/11. It has become a legal term to expand the jurisdiction of the AUMF and cover an ever-expanding number of terrorist groups. Thus, the “end of hostilities” is unforeseeable and may not even exist, since the United States keeps attacking current and new terrorist groups. Terrorism, as a tactic, doesn’t end — especially since the definition of the word “terrorism” is fuzzy — so a war against it may never end.

According to a May 2010 UN report, international law does not permit waging war against nebulous, stateless groups like terrorist organizations. However, last year, a Justice Department attorney admitted in a federal court hearing that the War on Terror could last 100 years and former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis said this war has no time limitation. The United States is involved in a global, endless war against a nebulous enemy — terrorism — and Guantánamo is the de facto prisoner-of-war camp for that war. The indefinite detainees are, therefore, prisoners of war in an endless war.

Meanwhile, the Democrat-controlled House recently passed an amendment that repeals the 2001 AUMF. However, it’s unlikely to pass the Senate, which is controlled by Republicans, and President Trump will most likely veto such legislation curtailing his war powers since his administration is contemplating war with Iran. Since last May and June, Trump has sent more than 2,000 additional troops to the Middle East to counter Iran. Trump already showed a willingness to veto legislation limiting his war powers. In April, Trump vetoed congressional legislation that would have ended the United States’s military involvement in and support for Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen. The Senate failed to override the veto.

Trump’s rhetoric on Guantánamo during the 2016 campaign trail was far more belligerent than Obama’s. While Obama criticized Guantánamo and torture, Trump openly embraced torture. A year after Trump took office, in January 2018, he signed an executive order to keep Guantánamo open, which nullified Obama’s executive order to close the prison. Despite the difference in rhetoric and conflicting executive orders, Trump has continued the Guantánamo system of indefinite detention maintained by Bush and Obama. The Supreme Court recently refused to hear a lawsuit by Moath Hamza Ahmed al-Alawi challenging his indefinite detention at Guantánamo, which puts the U.S. legal system on autopilot for permitting life imprisonment without trial.

So, one major reason why Guantánamo is not a central issue in the 2020 presidential campaign is because perpetual war, Guantánamo and indefinite detention have become permanent features of U.S. foreign policy: Without pressure from below, the state has no reason to curb its own abuses. (It’s worth noting that even before the current era of “forever wars,” this continent has arguably been in a perpetual state of war since the European colonization of the Americas and genocide of the Native Americans.)

Aging Prisoners in Indefinite Detention

Guantánamo has been open for over 17 years, and the men incarcerated there are getting older. The Pentagon is now considering plans to create a medical center for elderly detainees, anticipating that indefinitely detained people will age and die at the prison. Some Guantánamo detainees are already well into their fifties and will require a litany of medical treatment, especially given the abuse they have suffered in prolonged detention. Hambali, a 55-year-old Indonesian man detained for his ties to the militant group Jemaah Islamiyah, “is due for a knee replacement,” according to The New York Times, which his attorney says results from his time in CIA captivity, when the agency shackled him at the ankles.

Congress, in fact, is considering whether to allow Guantánamo detainees to be moved temporarily to U.S. soil for urgent medical treatment. The Senate Armed Services Committee recently approved a provision within the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act “that would allow temporary medical transfers to the United States,” according to The New York Times.

The issue of aging prisoners is not restricted to Guantánamo, of course. Many thousands of elderly people are incarcerated in U.S. domestic prisons. Thanks to long sentences driven by the war on drugs and “tough on crime” policies, the U.S. prison system is facing an aging population. In 2013, the prison population over the age of 50 rose to over 243,000. Between 1999 and 2015, the number of prisoners older than 55 increased by 280 percent. It’s expected that one-third of the U.S. prison population will be over the age of 50 by 2030. Michelle Chen writes at The Nation that prison is “an environment of ‘accelerated aging’ — when preventable suffering becomes chronic deterioration. Sometimes prisoners’ vulnerability exposes them to abuse and exploitation from predatory security officers or fellow inmates.”

Older prisoners, upon being released, are far less likely to be re-arrested and sent back to prison than younger prisoners. Prisoners older than 65 have very low recidivism rates. According to the Osborne Association, “Nationwide, 43.3 percent of all released individuals recidivate within three years, while only seven percent of those aged 50-64 and four percent of those over 65 return to prison for new convictions — the lowest rates among all incarcerated age demographics.” The older a prisoner is, the less likely they are to reenter prison.

The incarceration of aging people in the prison at Guantánamo Bay — and across the U.S. — raises the question: What’s the point? Former political prisoner Laura Whitehorn, who organizes with the advocacy group Release Aging People in Prison, told Truthout that the incarceration of older people reflects the larger injustices of the system.

“The inhumanity of incarcerating people as they age and their health declines … does reveal the U.S. belief that we can solve social problems by locking them up,” Whitehorn said. “The number of older incarcerated people (let’s be clear that we are talking about a population that is disproportionately African Americans and other people of color) will continue to rise if the current reliance on revenge and endless punishment is not overturned.”

Where the Democratic presidential candidates stand on Guantánamo is important. Should a Democrat win the 2020 election, they will have, in their hands, the power to continue indefinitely detaining dozens of men in Guantánamo — and, relatedly, to incarcerate limitless numbers of people at home and wage global perpetual war. The question remains whether Democratic presidential candidates will raise Guantánamo during tonight’s debates or at some future point in the 2020 campaign.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.