For more than 85 years, the Highlander Research and Education Center in Tennessee has been leading the fight for social, racial and economic justice. Co-executive directors of the Highlander Center, Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson and Reverend Allyn Maxfield-Steele, recently appeared on my show to discuss Southern organizing efforts around the 2018 midterms, why Black women were so integral to what the media termed a “blue wave,” and the importance of rural ownership of internet infrastructure. A lightly edited transcription of our conversations appears below.

Laura Flanders: It’s always important for me to try to check in with people who actually live in the South, because the stuff that you read and hear when you live in New York is never anywhere close to what I actually experience when I leave these parts. The fact that our media is so Northeast-focused is a serious problem. We are now in 2019, but just to take us back a little, what did you make of the midterm elections? Was it a blue wave?

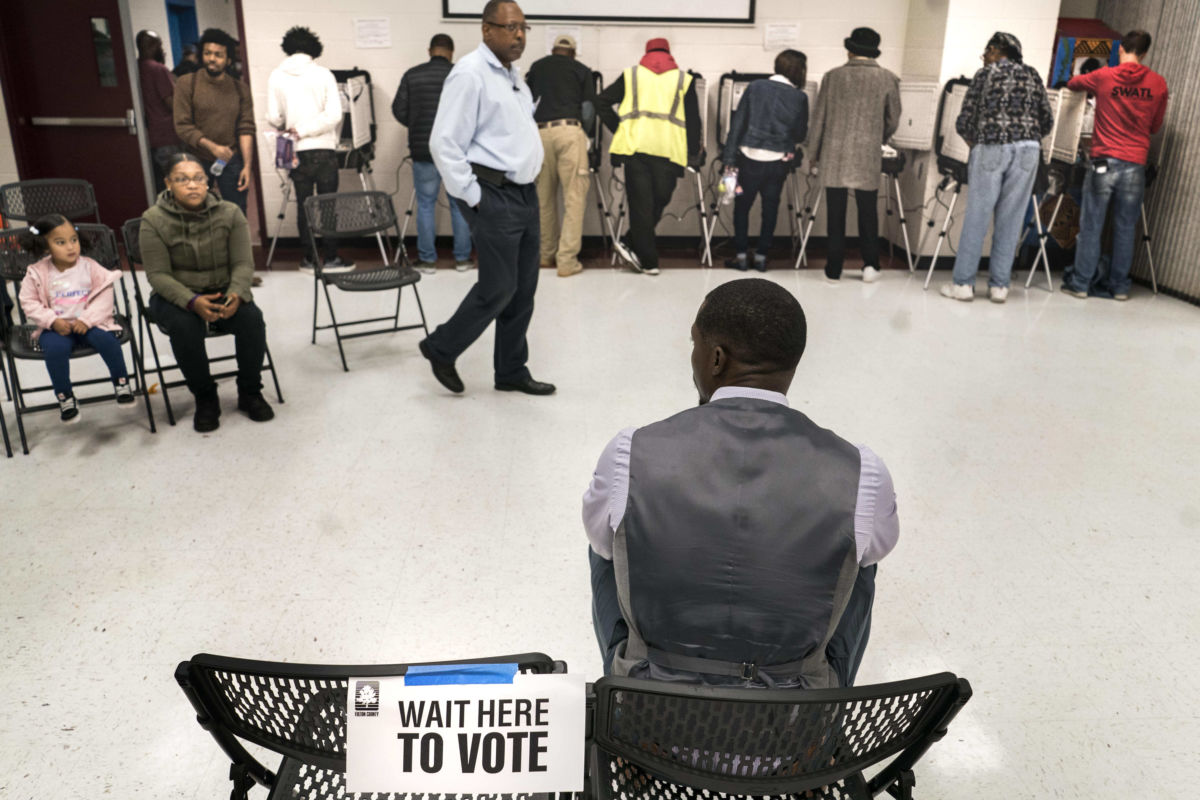

Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson: Yeah, I think it absolutely was not a blue wave. I think it was evidence of the incredible impact that Black women’s labor can have on the world. When we believe in a dream, when we focus on not just catering to the center and the right, but actually talk to our people, and talk about how we can meet their direct needs, they’ll believe us and they’ll throw down for us. And even if we do all that work, the white right will steal an election — over, and over, and over again.

So, before we get to the white right and stealing, let’s go back to Black women’s work. When I think about this coverage that we got of campaigns, like in Georgia, around Stacey Abrams and many more, we hear that Democrats turned out their base. That Democratic activists, maybe led by women of color, turned out their base for this candidate that everyone believed in. Are you saying that wasn’t what happened?

Woodard Henderson: If we look at primaries — the Democratic Party doesn’t get involved in primaries, right? So, who got Stacey to the general election? Who found Stacey Evans to run against her? There’s 159 counties in Georgia; Stacey Abrams won 153. She beat Stacey Evans in her home district. It took Black women, and other women of color, saying, “We are committed to flanking and supporting the Black women that are running Stacey Abrams’s campaign and Stacey Abrams is a Black woman that we trust and believe in, and we value her leadership.”

But Georgia’s only one of those stories, right? Even before Georgia, the Alabama race with Roy Moore and Doug Jones…. The Democrats took a lot of credit for that as well, when what we know is that it was … a multi-sector coalition of Black folks — particularly led by Black women and formerly incarcerated people — that won that fight. If you look at Florida, Amendment 4 or [Andrew] Gillum, it was this broad Black coalition and people fighting anti-Blackness, and fighting for Black leadership, that came together and made the impossible possible. And so, did Democrats show up? Maybe. But was that the reason that we saw these astronomical gains? Absolutely not, that was the people power.

Let’s hear about some of the reasons why…. What have you heard? Why did people get so involved — whether you’re talking Andrew Gillum in Florida, or Stacey Abrams or Doug Jones — what’s the motivation?

Allyn Maxfield-Steele: I think people are hungry for something more. More than what they’ve been getting. I think people are remembering in this moment that there is a deep tradition of resistance in the South around a whole range of things. Whether it’s Black liberation work, poor people’s organizing, a whole range of things that people are starting to collectively talk about again, in a way that has been silenced, it’s been repressed. And I think — like to your point when you opened up the conversation around media and storytelling outside of the Northeast, people have been telling the story about us, and for us, but I think folks are really getting excited to talk to each other in the South again. So that, I think, brings a level of inspiration for people … whether it’s an electoral fight, or whether it’s something else — people are really wanting to get into creative solutions to the conditions we’ve inherited in this moment. So, I think people are really hyped.

LF: That speaks to me about what happens next, or what we might see next. You want to come in on that, Ash-Lee?

Woodard Henderson: Yeah, I think it’s what many Southerners have been saying for a long time. It’s not that Highlander in particular is doing anything new. It’s that we’re doing it to scale and in innovative ways. So, I think what we’re hearing in the region is that we have to have an electoral justice mindset. We don’t have the luxury to throw that tactic away.

So that split we sometimes hear about, between “movement work” and “electoral work,” that’s what you’re talking about.

Woodard Henderson: Yeah, and to be quite frank, the idea of the blue wave — we’re not just trying to build up a Democratic Party, what we’re trying to do is build independent political power for our folks.

Now was that just you?

Woodard Henderson: No, I think that’s the movement for Black Lives, the Southern Movement Assembly…. We have a whole tier of our work around building participatory democracy and movement governance. So, I think all of that is harm reduction. Most of us are not confused that the state has never done a whole hell of a lot for us. What we are sure of is that we can’t afford to throw away tactics. When my elders and ancestors said, “by any means necessary,” they meant by all the means. Everything in my tactical toolbox, because the state, the white right, those folks are using every tactic that they’ve got. So, we’ve got to meet sophistication with sophistication, as Willy Baptiste said. I think that means we have to have an electoral justice project, or the Movement for Black Lives, it’s got fellows all over the South and all over the country that are winning campaigns. It means that we’re beating down the doors and doing the harm reduction work in progressive policy land. It also means building alternatives to the thing that’s harming us.

So, to go back to the history for a little bit, the 1930s, when the Highlander Center was started. We have seen a real change in how we understand the struggle. If you go back to that period, it felt like it was a very broad agenda. When you talk about building an independent movement, it was also a broad building [of] a new South, not just passing a few laws or getting a few people elected. Yet that seems to be so often what we’ve been shrunk back down to, people on the left, or with the critique of the right. Where do you stand now about where the lines of struggle are, and particularly on economics?

Maxfield-Steele: I think that’s real. I think when we started, it was about transforming the social-leaning economic order. That’s the same thing we’re doing now, whatever we’re inheriting. I think that when you get into the question of what the role of Highlander has been, it has been to help people develop different kinds of relationships and arrangements so that we could replicate the (lowercase-“d”) democratic practice that we’re in this particular space toward what it means to build a different kind of state, or what it means to build a different kind of society.

I’m just thinking in the ’30s, the Highlander Center had people from the Communist Party, had socialists, had organized parties of the left that have been studiously wiped out in the decades since, and the ideas of transformation have been radically changed in that period, too.

Woodard Henderson: Yeah, I feel excited about this conversation because it’s an opportunity to highlight some good stuff that we’ve been saying. For example, the West Virginia teacher’s strike. People would’ve said that was impossible. They definitely would’ve said a wildcat strike is. And they would’ve said that West Virginia’s Trump country. These teachers said, “Enough”…. In a right-to-work state, their young people supported, families of those young people supported, the community supported. But then when the union sold out, if that’s the narrative of what happened, they were like, “Oh no, that’s not what we said we wanted,” and they continue to strike.

Right, we didn’t just want a bit for us.

Woodard Henderson: Right. We’re talking about the whole economic infrastructure. That shows us a couple of things. One is, it tells us that everything they’re telling us about Appalachia, particularly West Virginia under a microscope, is not true.

Secondly, what it tells me is that the conversations I heard, especially from the young people that were getting involved in the strike, wasn’t just like, “Oh, I love the Democratic Party,” or “I love democratic socialism,” quite frankly. It was, “My granddad was a [United Mine Worker] member, and I remember him going out on strike. That’s my legacy.”

So even if they don’t understand everything, all the details of why capitalism is terrible, why these other economic alternatives are more possible and better for them, what they know is that they’re connected to a radical legacy of resistance. They’re literally remembering what’s been stolen from them.

I think that’s why Black people that were disengaged and — not apathetic, but not hopeful about electoral work working, because quite frankly, it didn’t. It worked exactly like it’s supposed to, to keep them disenfranchised. They were like, “I believe Stacey, and my grandmamma was waiting in line for four hours, who am I to complain?” There’s like a literal remembering that’s happening with a new generation of the stewards of the Southern Freedom Movement, and we’re seeing that rise….

Kinship is often built over things you share. You’re actually sharing something else right now … which is broadband. Can you talk about that initiative, which I think also gets to this question of economic self-empowerment and building a new economic system?

Maxfield-Steele: So there’s a task force called SEAD [Task Force] — the Sustainable & Equitable Agricultural Development Task Force — that’s based out of East Tennessee. They had a rural broadband campaign that started several years ago and had some legislative work they were working on and pushing really hard. Then there was the question of infrastructure. What does it actually mean to build our own infrastructure around internet connectivity in rural Appalachia? There’s all kinds of stuff you can read and write about around the lack of connectivity for folks.

Woodard Henderson: Intentional lack.

Maxfield-Steele: Intentional lack, and corporate control of what is available. So, we built a tower on our property. We didn’t make it ourselves, but we ordered a tower, put it in the ground, and that tower then relays Wi-Fi connectivity down to our buildings. We’re in the middle of a fantastic experiment around it and also leveraging our own infrastructure to support other projects that will come down the road.

Woodard Henderson: I think what’s real is, we weren’t just talking about rural broadband for the people. We literally needed it. We didn’t have access.

And the people in the valleys around you, too. Will you eventually be able to offer it to them?

Woodard Henderson: They’re already on our tower. I think we’ve got about 60 folks, or 60 residents.

What’s the price difference?

Woodard Henderson: It’s significant. For Highlander, we were paying a company that was terrible to us to the tune of like at least $800 a month just for the internet. But now I can lay in my bed at my house there and watch Netflix, answer emails, and FaceTime my niece; it’s changed what is possible. It’s our tower. I think that most people are paying in the $80 range to the company that’s providing our back haul. And we’re fundraising to be able to support covering peoples’ connectivity fees and that kind of stuff, so that all they have to do is make sure that they can pay it monthly.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $41,000 in the next 5 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.